TABLE OF CONTENTS

・The derivative of \( x^n \)

・The derivatives of trigonometric functions

・The derivatives of \( e^x \) and \( \ln x \)

・Logarithmic differentiation

・The derivatives of inverse trigonometric functions

・\( n \)th order derivative function

Mathematics articles that help in reading this article

・Numerical Computation: Ep. 1, Ep. 2, Ep. 4, Ep. 5, Ep. 6

・Numerical Computation: Ep. 1, Ep. 2, Ep. 4, Ep. 5, Ep. 6

The derivative of \( x^n \)

\[ \left( x^n \right) ' = n x^{n-1} \ \ ( n \ \text{is an integer,} \ x \ \text{is a real number} ) \]

The derivative of \( x^n \) is calculated by subtracting 1 from the exponent of \( x \) and then

multiplying by the original exponent.

To prove this formula, we first handle the case where \( n \gt 0 \), then move on to the case where \( n = 0

\).

Finally, we'll use these results to address the case where \( n \lt 0 \).

Let's start with the case where \( n \gt 0 \).

[1] When \( n = 1 \):

Since \( x^1 = x \), \[ \begin{align} (x)' &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{(x + h) - x}{h} \\\\ &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{h}{h} \\\\ &= \lim _{h \to 0} 1 \\\\ &= 1 \\\\ &= 1 \times x^{1-1} \\\\ \end{align} \] Therefore, when \( n = 1 \), the formula \( \left( x^n \right) ' = n x^{n-1} \) holds.

[2] Assume for any natural number \( k \), \[ \left( x^k \right) ' = k x^{k-1} \] holds. Then, for \( n = k+1 \) \[ \begin{align} (x^{k+1})' &= (x^k \times x)' \\\\ &= (x^k)' \times x + x^k \times (x)' \\\\ &= k x^{k-1} \times x + x^k \times 1 \\\\ &= k x^k + x^k \\\\ &= (k+1)x^k \\\\ &= (k+1)x^{(k+1)-1} \end{align} \] Thus, the formula \( \left( x^n \right) ' = n x^{n-1} \) also holds for \( n = k + 1\).

From [1] and [2], the formula \( \left( x^n \right) ' = n x^{n-1} \) holds for any natural number \( n \).

Since \( x^1 = x \), \[ \begin{align} (x)' &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{(x + h) - x}{h} \\\\ &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{h}{h} \\\\ &= \lim _{h \to 0} 1 \\\\ &= 1 \\\\ &= 1 \times x^{1-1} \\\\ \end{align} \] Therefore, when \( n = 1 \), the formula \( \left( x^n \right) ' = n x^{n-1} \) holds.

[2] Assume for any natural number \( k \), \[ \left( x^k \right) ' = k x^{k-1} \] holds. Then, for \( n = k+1 \) \[ \begin{align} (x^{k+1})' &= (x^k \times x)' \\\\ &= (x^k)' \times x + x^k \times (x)' \\\\ &= k x^{k-1} \times x + x^k \times 1 \\\\ &= k x^k + x^k \\\\ &= (k+1)x^k \\\\ &= (k+1)x^{(k+1)-1} \end{align} \] Thus, the formula \( \left( x^n \right) ' = n x^{n-1} \) also holds for \( n = k + 1\).

From [1] and [2], the formula \( \left( x^n \right) ' = n x^{n-1} \) holds for any natural number \( n \).

In [1], we showed that the formula holds when \( n = 1 \).

Next, in [2], we assumed the formula holds for \( n = k \) and then showed that it also holds for \( n = k +

1 \).

From this, we know the formula holds for \( n = 2 \) by combining [1] and [2]. Applying the same reasoning

again shows it holds for \( n = 3 \).

By continuing this process repeatedly, we can conclude that the formula holds for any natural number \( n

\).

This method of proof is generally called mathematical induction.

When \( n = 0 \), \( x^0 = 1 \), then,

\[ \begin{align}

(1)' &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{1 - 1}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{0}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} 0 \\\\

&= 0 \\\\

&= 0 \times x^{0-1} \\\\

\end{align} \]

Therefore, when \( n = 0 \), the formula \( \left( x^n \right) ' = n x^{n-1} \) also holds.

The \( 1-1 \) in the numerator of the first line of the equation becomes easier to understand if you

consider the constant function \( f(x) = 1 \).

For this function, substituting \( x+h \) for the variable \( x \) still gives the value 1, so the numerator

of the derivative, \( f(x+h) - f(x) \), becomes \( 1-1 \).

At the end of the calculation, since multiplying zero by anything results in zero, we multiply by \( x^{0-1} \) to match the form of the formula.

At the end of the calculation, since multiplying zero by anything results in zero, we multiply by \( x^{0-1} \) to match the form of the formula.

To prove that

\[ \left( x^n \right) ' = n x^{n-1} \]

holds for \( n \lt 0 \), it is sufficient to show that

\[ \left( x^{-m} \right) ' = -m x^{-m-1} \ \ \text{(} \ m \ \text{is a natural number)}\]

also holds.

\[ \begin{align}

\left( x^{-m} \right) ' &= \left( \frac{1}{x^m} \right) ' \\\\

&= \frac{(1)' \times x^{m} - 1 \times \left( x^m \right) '}{\left( x^m \right)^2} \\\\

&= \frac{0 \times x^{m} - 1 \times m x^{m-1}}{x^{2m}} \\\\

&= - \frac{m x^{m-1}}{x^{2m}} \\\\

&= - m x^{-m-1}

\end{align} \]

By substituting \( n = -m \), we can make use of the quotient rule for differentiation.

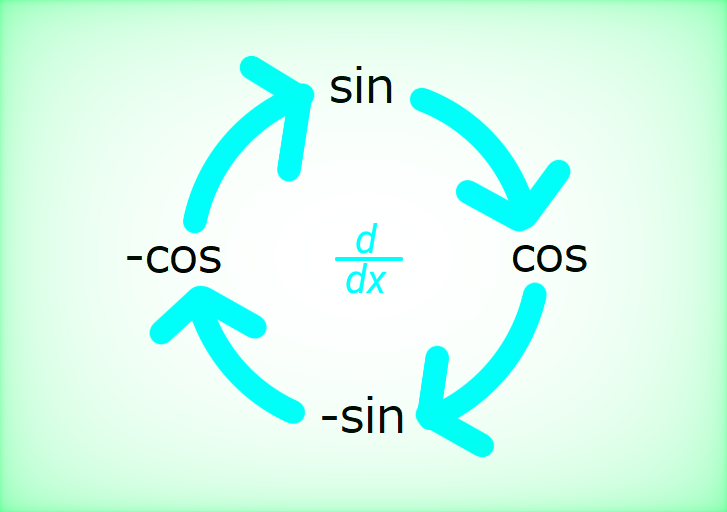

The derivatives of trigonometric functions

\[ \begin{align}

&\left( \sin x \right) ' = \cos x \ \ (x \ \rm is \ real.) \\\\

&\left( \cos x \right) ' = - \sin x \ \ (x \ \rm is \ real.) \\\\

&\left( \tan x \right) ' = \frac{1}{\cos ^2 x} \ \ (\rm Where \ \ \it x \ \ \rm is \ a \ real \ number \

except \ \frac{(2 \it n \rm -1) \pi}{2} \ \rm in \ which \ \it n \ \rm is \ an \ integer.)

\end{align} \]

\[ \tan x = \frac{\sin x}{\cos x} \]

This definition holds only when \( \cos x \neq 0 \).

Therefore, if \( n \) is an integer,

\[ x = \frac{(2 \it n \rm -1) \pi}{2} \]

makes the derivative of the tangent function undefined.

\[ \begin{align}

\left( \sin x \right) ' &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{\sin \left( x+h \right) - \sin x}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{2 \cos \frac{\left( x+h \right) + x}{2} \sin \frac{\left( x+h \right) -

x}{2}}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{2 \cos \frac{2x+h}{2} \sin \frac{h}{2}}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} 2 \cos \frac{2x+h}{2} \frac{\sin \frac{h}{2}}{\frac{h}{2}} \times \frac{1}{2} \\\\

&= 2 \cos \frac{2x}{2} \times 1 \times \frac{1}{2} \\\\

&= \cos x

\end{align} \]

In the second line, we used the identity that rewrites a difference as a product.

In the fourth line, we arranged the expression to apply the sinc function limit formula:

\[ \lim _{x \to 0} \frac{\sin x}{x} = 1 \]

\[ \begin{align}

\left( \cos x \right) ' &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{\cos \left( x+h \right) - \cos x}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} - \frac{2 \sin \frac{\left( x+h \right) + x}{2} \sin \frac{\left( x+h \right) -

x}{2}}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} - \frac{2 \sin \frac{2x+h}{2} \sin \frac{h}{2}}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} - 2 \sin \frac{2x+h}{2} \frac{\sin \frac{h}{2}}{\frac{h}{2}} \times \frac{1}{2} \\\\

&= - 2 \sin \frac{2x}{2} \times 1 \times \frac{1}{2} \\\\

&= - \sin x

\end{align} \]

\[ \begin{align}

\left( \tan x \right) ' &= \left( \frac{\sin x}{\cos x} \right) ' \\\\

&= \frac{\left( \sin x \right)' \cos x - \sin x \left( \cos x \right) '}{\cos ^2 x} \\\\

&= \frac{\cos x \cos x - \sin x \left( - \sin x \right) }{\cos ^2 x} \\\\

&= \frac{\cos ^2 x + \sin ^2 x}{\cos ^2 x} \\\\

&= \frac{1}{\cos ^2 x}

\end{align} \]

The derivatives of \( e^x \) and \( \ln x \)

\[ \lim _{x \to 0} \frac{e^x - 1}{x} = 1 \]

\[ \lim _{x \to 0} \left( 1+x \right) ^{\frac{1}{x}} = e \]

\[ \begin{align}

\lim _{x \to 0} \frac{e^x - 1}{x} &= 1 \\\\

\lim _{x \to 0} e^x - 1 &= \lim _{x \to 0} x \\\\

\lim _{x \to 0} e^x &= \lim _{x \to 0} \left( 1+x \right) \\\\

e &= \lim _{x \to 0} \left( 1+x \right) ^{\frac{1}{x}}

\end{align} \]

For \( f(x) = e^x \), the slope of the tangent line at \( x = 0 \), which is the derivative at that

point, is 1. Therefore,

\[ \begin{align}

f'(0) &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{f \left( 0 + h \right) - f(0)}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{e^{0+h} - e^0}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{e^{h} - 1}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{x \to 0} \frac{e^{x} - 1}{x} = 1

\end{align} \]

\[ \begin{align}

&\left( e^x \right) ' = e^x \ \ ( x \ \rm{is \ real.} ) \\\\

&\left( \ln x \right) ' = \frac{1}{x} \ \ ( x \rm \gt 0 )

\end{align} \]

\[ \begin{align}

\left( e^x \right) ' &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{e^{x+h} - e^x}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{e^x e^h - e^x}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{e^{x} \left( e^h - 1 \right) }{h} \\\\

&= e^{x} \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{e^h - 1}{h} \\\\

&= e^{x} \times 1 = e^x

\end{align} \]

In the fourth line, \( e^x \), which does not depend on \( h \), is taken outside the limit, creating a

form where the previously derived limit formula can be applied.

\[ \begin{align}

\left( \ln x \right) ' &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{\ln \left( x+h \right) - \ln x}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{\ln \frac{x+h}{x}}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{1}{h} \ln \left( 1 + \frac{h}{x} \right) \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \ln \left( 1 + \frac{h}{x} \right) ^{\frac{1}{h}} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \ln \left\{ \left( 1 + \frac{h}{x} \right) ^{\frac{x}{h}} \right\} ^{\frac{1}{x}}

\\\\

&= \ln e^{\frac{1}{x}} \\\\

&= \frac{1}{x} \ln e = \frac{1}{x}

\end{align} \]

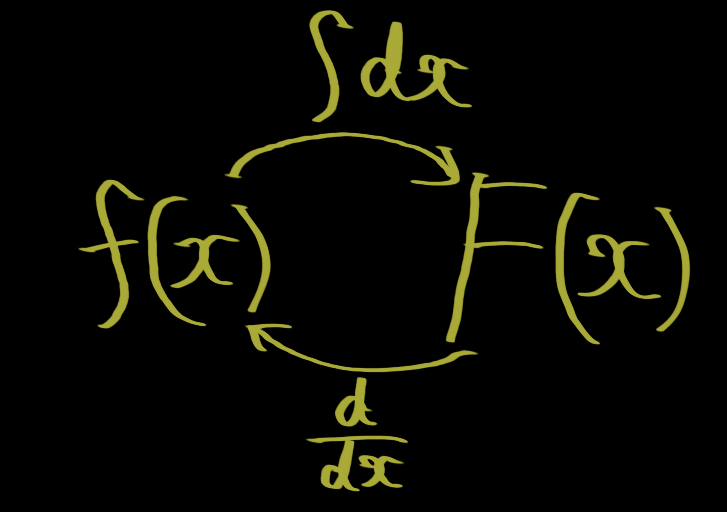

Logarithmic differentiation

\[ \left( x^a \right) ' = a x^{a-1} \ \ ( a \ \rm{is} \ \rm{real, \ and} \ \it{x} \ \rm{is \ a \

positive \ real \ number.} )\]

\[ \left( a^x \right) ' = a^x \ln a \ \ ( x \ \rm{is \ real, \ and} \ \it{a} \ \rm{is \ a \ positive \

real \ number.} ) \]

The first one has the same form as the derivative of \( x^n \) we found earlier.

However, note that the exponent has been extended from integers to real numbers, and the domain is

restricted to positive real numbers.

Let \( y = x^a \), and take the natural logarithm of both sides:

\[ \begin{align}

\ln y &= \ln x^a \\\\

\ln y &= a \ln x

\end{align} \]

Differentiating both sides with respect to \( x \):

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{d}{dx} \left( \ln y \right) &= \frac{d}{dx} \left( a \ln x \right) \\\\

\end{align} \]

Now, if we set \( v = \ln y \), then by the chain rule, the left-hand side becomes:

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{d}{dx} \left( \ln y \right) &= \frac{dv}{dx} \\\\

&= \frac{dv}{dy} \frac{dy}{dx} \\\\

&= \left( \ln y \right) ' y' \\\\

&= \frac{1}{y} y'

\end{align} \]

Thus,

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{1}{y} y' &= \frac{d}{dx} \left( a \ln x \right) \\\\

\frac{1}{y} y' &= a \frac{d}{dx} \left( \ln x \right) \\\\

\frac{1}{y} y' &= \frac{a}{x} \\\\

y' &= \frac{a}{x} \times y \\\\

&= \frac{a}{x} x^a = a x^{a-1}

\end{align} \]

We used the derivative notation \( \frac{d}{dx} \), which is especially useful when dealing with three or

more variables, as it clearly indicates with respect to which variable the differentiation is performed.

Also, since logarithmic differentiation starts by taking the natural logarithm, be careful that it can only

be applied to functions whose values are positive real numbers.

Let \( y = a^x \), and take the natural logarithm of both sides:

\[ \begin{align}

\ln y &= \ln a^x \\\\

\ln y &= x \ln a

\end{align} \]

Differentiating both sides with respect to \( x \):

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{d}{dx} \left( \ln y \right) &= \frac{d}{dx} \left( x \ln a \right) \\\\

\end{align} \]

Now, if we set \( v = \ln y \), then by the chain rule, the left-hand side becomes:

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{d}{dx} \left( \ln y \right) &= \frac{1}{y} y'

\end{align} \]

Thus,

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{1}{y} y' &= \frac{d}{dx} \left( x \ln a \right) \\\\

\frac{1}{y} y' &= \ln a \frac{d}{dx} \left( x \right) \\\\

\frac{1}{y} y' &= \ln a \\\\

y' &= y \ln a = a^x \ln a

\end{align} \]

The derivatives of inverse trigonometric functions

\[ \begin{align}

&\left( \sin ^{-1} x \right) ' = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}} \ \ ( -1 \lt x \lt 1 ) \\\\

&\left( \cos ^{-1} x \right) ' = - \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}} \ \ ( -1 \lt x \lt 1 ) \\\\

&\left( \tan ^{-1} x \right) ' = \frac{1}{1 + x^2} \ \ ( - \infty \lt x \lt \infty )

\end{align} \]

Let \( y = \sin ^{-1} x \). Then \( x = \sin y \), and by the formula for the derivative of an inverse function,

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{dy}{dx} = \cfrac{1}{\cfrac{dx}{dy}}

= \frac{1}{\cos y}

\end{align} \]

Since, by the definition of the inverse sine function, \( - \pi / 2 \leq y \leq \pi / 2 \), we have \( \cos y \geq 0 \).

Therefore,

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{1}{\cos y}

= \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\sin ^2 y}}

= \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}

\end{align} \]

Let \( y = \cos ^{-1} x \). Then \( x = \cos y \), and by the formula for the derivative of an inverse function,

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{dy}{dx} = \cfrac{1}{\cfrac{dx}{dy}}

= - \frac{1}{\sin y}

\end{align} \]

Since, by the definition of the inverse cosine function, \( 0 \leq y \leq \pi \), we have \( \sin y \geq 0 \).

Therefore,

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{dy}{dx} = - \frac{1}{\sin y}

= - \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\cos ^2 y}}

= - \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}

\end{align} \]

Let \( y = \tan ^{-1} x \). Then \( x = \tan y \), and by the formula for the derivative of an inverse function,

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{dy}{dx} = \cfrac{1}{\cfrac{dx}{dy}}

= \cos ^2 y

= \frac{1}{1 + \tan ^2 y}

= \frac{1}{1 + x^2}

\end{align} \]

\( n \)th order derivative function

\[ n \text{th order derivative function}\]

Define the \( \boldsymbol n \)th order derivative function \( f^{\left( n \right)} (x) \)

of the function \( y = f(x) \) with \( n \) as a natural number.

[1] \( f^{\left( 1 \right) } (x) = f'(x) \)

[2] \( f^{\left( n \right) } (x) = \left\{ f^{\left( n - 1 \right) } (x) \right\} ' \)

Other symbols representing the \( n \)th order derivative function are \( y^{\left( n \right)} \), \( \frac{d^n y}{dx^n} \) and \( \frac{d^n}{dx^n} f(x) \).

[1] \( f^{\left( 1 \right) } (x) = f'(x) \)

[2] \( f^{\left( n \right) } (x) = \left\{ f^{\left( n - 1 \right) } (x) \right\} ' \)

Other symbols representing the \( n \)th order derivative function are \( y^{\left( n \right)} \), \( \frac{d^n y}{dx^n} \) and \( \frac{d^n}{dx^n} f(x) \).

\[ \begin{align}

C^n \text{-function}

\end{align}\]

If the \( n \)th derivative \( f^{\left( n \right) } (x) \) of a function \( y = f(x) \) exists, then

\( f(x) \) is said to be \( \boldsymbol n \)-times differentiable.

Furthermore, if \( f^{\left( n \right) } (x) \) is continuous, \( f(x) \) is called an \( \boldsymbol n

\)-times

continuously differentiable function, or a \( \boldsymbol C^n \)-function.

In addition, if the \( m \)th derivative \( f^{\left( m \right) } (x) \) exists for every natural number

\( m \), then \( f(x) \) is called a \( \boldsymbol C^{\infty} \)-function.

References:

[1] James R. Newman, THE UNIVERSAL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MATHEMATICS, George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1964

[2] 石村園子, やさしく学べる微分積分, 共立出版, December 25, 1999

[3] 難波 誠, 数学シリーズ 微分積分学, 裳華房, January 20, 2009