TABLE OF CONTENTS

・Derivative of a function of one variable

・Equivalent condition for differentiability

・Sum rule and constant factor rule

・Product rule and quotient rule

・Chain rule for composite functions

・Inverse function rule

Derivative of a function of one variable

\[ \text{Derivative}\]

For a function of one variable \( y = f(x) \) whose domain is a real interval containing \( x = a \),

if

\[ \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{f(a + h) - f(a)}{h} \]

exists, then \( f(x) \) is differentiable at \( x = a \), and this limit is called the

derivative of \( f(x) \) at \( a \), and is denoted by \( f ' (a) \).

Derivative of \( f(x) \) at \( a \) is equal to the slope of the tangent line at \( x = a \) of \( f(x)

\).

A real interval is a range of real numbers expressed using inequalities.

\[ \text{Real interval}\]

A method for representing a range of real numbers. Using an inequality involving a variable \( x \) and

constants \( a \) and \( b \), it can be classified as follows.

\( [a,b] \) : \( a \leqq x \leqq b \)

\( (a,b] \) : \( a \lt x \leqq b \)

\( [a,b) \) : \( a \leqq x \lt b \)

\( (a,b) \) : \( a \lt x \lt b \)

\( [a,b] \) : \( a \leqq x \leqq b \)

\( (a,b] \) : \( a \lt x \leqq b \)

\( [a,b) \) : \( a \leqq x \lt b \)

\( (a,b) \) : \( a \lt x \lt b \)

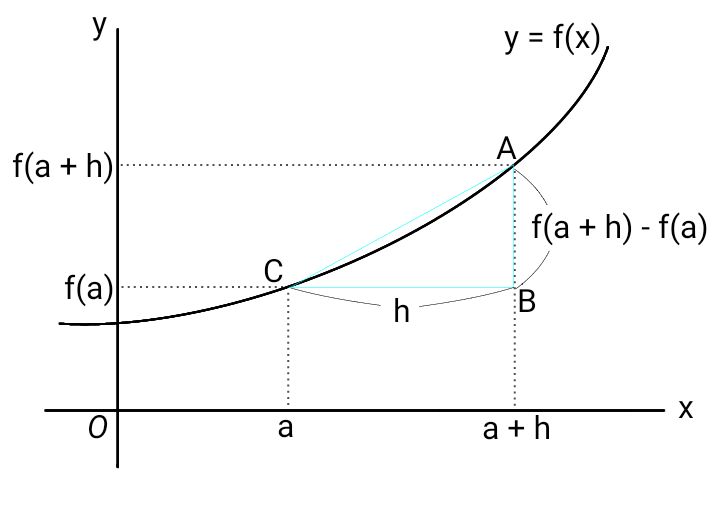

From the diagram, the expression \[ \frac{f(a + h) - f(a)}{h} \] that appears in the definition of the

derivative represents the slope of \( \rm AC \).

As \( h \) approaches zero, the light blue triangle \( \rm ABC \) becomes extremely small, keeping the point

\( \rm C \) fixed.

At this point, the slope of \( \rm AC \) becomes equal to the slope of the tangent line to \( f(x) \) at \(

x = a \), which is known as the derivative.

The definition of the derivative is the limit as \( x \) approaches a certain value \( a \), so we need to

specify \( a \) each time.

However, to make general discussions easier, we consider the following function.

\[ \text{Derivative function}\]

If a function \( y = f (x) \) is differentiable at every points \( x \) in a real interval, the

function that corresponds the derivative \( f ' (x) \) to \( x \) is called the derivative

function of \( y = f (x) \), and is expressed as \( y' \), \( f '(x) \), \( \frac{dy}{dx} \), \(

\frac{df}{dx} \), \( \frac{d}{dx} f (x) \), and so on.

There are various notations for derivatives, and it's fine to use whichever is most convenient depending on

the context.

Also, finding the derivative \( y = f'(x) \) from \( y = f(x) \) is referred to as 'differentiating' the

function.

Equivalent condition for differentiability

\[ \begin{align}

\text{Equivalent condition for differentiability}

\end{align}\]

A necessary and sufficient condition for \( y = f(x) \) to be differentiable at \( x=a \) is that there

exists some \( \delta \gt 0 \) such that, on the real interval

\( (a - \delta , a + \delta) \), \( f(x) \) can be written in the form

\[ \begin{align}

f(x) = f(a) + (x-a) f'(a) + (x-a) B(x),

\end{align}\]

where \( B(x) \) is a function defined on \( (a - \delta , a + \delta) \) that is continuous at \( x=a

\) and satisfies \( B(a) = 0 \).

We now prove the equivalent condition for differentiability.

First, assume that \( f(x) \) is differentiable at \( x=a \). Define \( B(x) \) by

\[ B(x) =

\begin{cases}

\displaystyle \frac{f(x) - f(a)}{x-a} - f'(a) & (x \neq a) \\[1em]

\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ 0 & (x = a)

\end{cases} \]

Then,

\[ \begin{align}

\lim _{x \to a} B(x) &= \lim _{x \to a} \left\{ \frac{f(x) - f(a)}{x-a} - f'(a) \right\} \\\\

&= f'(a) - f'(a) \\\\

&= 0 = B(a)

\end{align}\]

so \( B(x) \) is continuous at \( x = a \). Moreover, on the interval \( (a - \delta , a + \delta) \), we

have

\[ \begin{align}

f(x) = f(a) + (x-a) f'(a) + (x-a) B(x)

\end{align}\]

Conversely, suppose that on the interval \( (a - \delta , a + \delta) \), the function \( f(x) \) can be written in the form \[ \begin{align} f(x) = f(a) + (x-a) A + (x-a) B(x) \end{align}\] where \( A \) is a constant. For \( x \neq a \), dividing both sides by \( x - a \) gives \[ \begin{align} \frac{f(x) - f(a)}{x-a} = A + B(x) \end{align}\] Taking the limit as \( x \to a \), and using the fact that \( B(x) \) is continuous at \( x = a \) with \( B(a) = 0 \), we obtain \[ \begin{align} \lim _{x \to a} \frac{f(x) - f(a)}{x-a} = A = f'(a) \end{align}\] Thus, \( f(x) \) is differentiable at \( x = a \).

Conversely, suppose that on the interval \( (a - \delta , a + \delta) \), the function \( f(x) \) can be written in the form \[ \begin{align} f(x) = f(a) + (x-a) A + (x-a) B(x) \end{align}\] where \( A \) is a constant. For \( x \neq a \), dividing both sides by \( x - a \) gives \[ \begin{align} \frac{f(x) - f(a)}{x-a} = A + B(x) \end{align}\] Taking the limit as \( x \to a \), and using the fact that \( B(x) \) is continuous at \( x = a \) with \( B(a) = 0 \), we obtain \[ \begin{align} \lim _{x \to a} \frac{f(x) - f(a)}{x-a} = A = f'(a) \end{align}\] Thus, \( f(x) \) is differentiable at \( x = a \).

Sum rule and constant factor rule

\[\text{Sum rule and constant factor rule} \]

If the functions \( f(x) \) and \( g(x) \) are differentiable on the real interval \( I \), then, with

\( c \) as a real constant, \( cf(x) \) and \( f(x) \pm g(x) \) are also differentiable on \( I \), and

the following equations hold.

\[ \left\{ cf(x) \right\} ' = c f'(x) \]

\[ \left\{ f(x) \pm g(x) \right\} ' = f'(x) \pm g'(x)\]

\[ \text{Proof of the constant factor rule}\]

\[ \begin{align}

\left\{ cf(x) \right\} ' &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{cf(x+h) - cf(x)}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{c \left\{ f(x+h) - f(x) \right\} }{h} \\\\

&= c \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h} \\\\

&= c f'(x)

\end{align}\]

\[\text{Proof of the sum rule}\]

\[ \begin{align}

\left\{ f(x) \pm g(x) \right\} ' &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{\left\{ f(x+h) \pm g(x+h) \right\} - \left\{

f(x) \pm g(x) \right\}}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{\left\{ f(x+h) - f(x) \right\} \pm \left\{ g(x+h) - g(x) \right\}}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h} \pm \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{ g(x+h) - g(x)}{h} \\\\

&= f'(x) \pm g'(x)

\end{align}\]

Product rule and quotient rule

\[\text{Product rule and quotient rule}\]

If the functions \( f(x) \) and \( g(x) \) are differentiable on the real interval \( I \), then \(

f(x)g(x) \) and \( \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} \) (where \( g(x) \neq 0 \)) are also differentiable on \( I \),

and the following equations hold:

\[ \left\{ f(x)g(x) \right\} ' = f'(x)g(x) + f(x)g'(x) \]

\[ \left\{ \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} \right\} ' = \frac{f'(x)g(x) - f(x)g'(x)}{\left\{ g(x) \right\} ^2 } \]

\[ \text{Proof of the product rule}\]

\[ \begin{align}

\left\{ f(x)g(x) \right\} ' &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{f(x+h)g(x+h) - f(x)g(x)}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{f(x+h)g(x+h) - f(x)g(x+h) + f(x)g(x+h) - f(x)g(x)}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{\left\{ f(x+h)- f(x) \right\} g(x+h) + f(x) \left\{ g(x+h) - g(x) \right\}}{h}

\\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \left\{ \frac{f(x+h)- f(x)}{h} g(x+h) + f(x) \frac{ g(x+h) - g(x) }{h} \right\} \\\\

&= f'(x)g(x) + f(x)g'(x)

\end{align}\]

The second line has \[ - f(x)g(x+h) + f(x)g(x+h) \] added to the numerator. This is effectively adding

zero, so it's perfectly valid to do this.

This adjustment allows us to rewrite the expression in the third and fourth lines in a form that matches the

definition of the derivative.

\[ \text{Proof of the quotient rule}\]

\[ \begin{align}

\left\{ \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} \right\} ' &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{\frac{f(x+h)}{g(x+h)} -

\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{f(x+h)g(x) - f(x)g(x+h)}{hg(x+h)g(x)} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{1}{g(x+h)g(x)} \frac{f(x+h)g(x) - f(x)g(x) + f(x)g(x) - f(x)g(x+h)}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{1}{g(x+h)g(x)} \frac{\left\{ f(x+h) - f(x) \right\} g(x) - f(x) \left\{ g(x+h)

- g(x) \right\} }{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{1}{g(x+h)g(x)} \left\{ \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h} g(x) - f(x) \frac{g(x+h) -

g(x)}{h} \right\} \\\\

&= \frac{1}{g(x)g(x)} \left\{ f'(x)g(x) - f(x)g'(x) \right\} \\\\

&= \frac{f'(x)g(x) - f(x)g'(x)}{\left\{ g(x) \right\}^2}

\end{align}\]

In the third line, as before, the term \[ - f(x)g(x) + f(x)g(x) \], which sums to zero, is added to the

numerator to set up the definition of the derivative.

Chain rule for composite functions

\[\text{Chain rule for composite functions}\]

Suppose that the function \( u = f(x) \) is differentiable on the real interval \( I \), the function

\( y = g(u) \) is differentiable on the real interval \( J \), and the image of \( u = f(x) \) is

included in \( J \).

In this case, the composite function \( y = g(f(x)) \) is differentiable on the real interval \( I \),

and the following equation holds.

\[ y' = g'(u)f'(x) \]

A function of the form \( y = g(f(x)) \) is called a composite function.

A composite function is only defined if the image of \( f \) is contained within the domain of \( g \).

Before proving the chain rule for composite functions, let's first establish the following preliminary

theorem.

If \( y = f(x) \) is differentiable at \( x = a \), then it is also continuous at \( x = a \).

To show that \( y = f(x) \) is continuous at \( x = a \), we need to prove

\[ \lim _{x \to a} f(x) = f(a) \]

Setting \( x = a + h \), we have \( h \to 0 \) as \( x \to a \), so it is sufficient to show

\[ \lim _{h \to 0} f(a+h) = f(a) \]

By the assumption that \( y = f(x) \) is differentiable at \( x = a \), we have

\[ \begin{align}

\lim _{h \to 0} \left\{ f(a+h) - f(a) \right\} &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{f(a+h) - f(a)}{h} \times h

\\\\

&= f'(a) \times 0 = 0

\end{align}\]

Therefore,

\[ \lim _{h \to 0} f(a+h) = f(a) \]

which completes the proof.

\[ \text{Proof of the chain rule for composite functions}\]

By assumption, \( g(u) \) is differentiable, so

\[ g'(u) = \lim _{k \to 0} \frac{g(u+k) - g(u)}{k} \]

exists. Now, let

\[ k = f(x+h) - f(x).\]

Since \( f(x) \) is differentiable by assumption, it is also continuous, which means

\[ \lim _{h \to 0} f(x+h) = f(x) .\]

Thus,

\[ \lim _{h \to 0} k = \lim _{h \to 0} \left\{ f(x+h) - f(x) \right\} = 0.\]

Therefore,

\[ \begin{align}

y' &= \lim _{h \to 0} \frac{g(f(x+h))-g(f(x))}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h,k \to 0} \frac{g(f(x)+k)-g(f(x))}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h,k \to 0} \frac{g(u+k)-g(u)}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h,k \to 0} \frac{g(u+k)-g(u)}{k} \times \frac{k}{h} \\\\

&= \lim _{h,k \to 0} \frac{g(u+k)-g(u)}{k} \times \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h} \\\\

&= g'(u)f'(x)

\end{align}\]

Inverse function rule

\[\text{Inverse function rule}\]

Let \( y = f(x) \) be a monotonic (increasing or decreasing) function on a real interval \( I \), and

assume that \( f \) is differentiable on \( I \).

Then the inverse function \( x = f^{-1}(y) \) is differentiable at those values of \( y \) that

correspond to points \( x \) where \( f'(x) \neq 0 \), and the following formula holds.

\[ x' = \frac{1}{y'} \]

\[\text{Proof of the derivative formula for inverse functions}\]

Consider a point \( a \) in the real interval \( I \) such that \( f'(a) \neq 0 \).

Let \( b = f(a) \).

Since \( y = f(x) \) is differentiable at \( x = a \), there exists some \( \delta \gt 0 \) such that, on the interval \( (a - \delta, a + \delta) \), we can write

\[ \begin{align}

y - b = (x-a) f'(a) + (x-a) B(x)

\end{align}\]

where \( B(x) \) is a function defined on \( (a - \delta, a + \delta) \), continuous at \( x = a \), and satisfying \( B(a) = 0 \).

Noting that \( f'(a) \neq 0 \) and \( x = f^{-1}(y) \), we obtain

\[ \begin{align}

y - b &= \left( f^{-1} (y) - a \right) f'(a) + \left( f^{-1} (y) -a \right) B\left( f^{-1} (y)

\right) \\\\

f^{-1} (y) - a &= \frac{1}{f'(a)} \left( y-b \right) - \frac{1}{f'(a)} \cdot \left( f^{-1} (y) -a

\right) B\left( f^{-1} (y) \right) \\\\

&= \left( y-b \right) \cdot \frac{1}{f'(a)} + \left( y-b \right) \cdot \frac{\left( f^{-1} (y) -a

\right) B\left( f^{-1} (y) \right)}{f'(a)\left( b-y \right)} \\\\

&= \left( y-b \right) \cdot \frac{1}{f'(a)} + \left( y-b \right) \cdot \frac{-B\left( f^{-1} (y)

\right)}{f'(a) \left\{ f'(a) + B\left( f^{-1} (y) \right) \right\}}

\end{align}\]

Now define

\[ \begin{align}

C(y) = \frac{-B\left( f^{-1} (y) \right)}{f'(a) \left\{ f'(a) + B\left( f^{-1} (y) \right) \right\}}

\end{align}\]

This function satisfies \( C(b) = 0 \) and is continuous at \( y = b \).

Therefore, the inverse function \( x = f^{-1}(y) \) is differentiable at \( y = b \), and

\[ x' = \frac{1}{y'} \]

holds.

You can also “explain” the derivative formula for inverse functions in the following way.

\[\text{Explanation of the derivative formula for inverse functions}\]

On a real interval \( I \), differentiate both sides of the equation

\( x = f^{-1}(y) \) with respect to \( x \):

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{d}{dx} (x) &= \frac{d}{dx} f^{-1} (y)

\end{align}\]

By the chain rule for composite functions,

\[ \begin{align}

1 &= \frac{df^{-1} (y)}{dy} \cdot \frac{dy}{dx}

\end{align}\]

Thus, if \( dy/dx \neq 0 \), then

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{df^{-1} (y)}{dy} &= \cfrac{1}{\cfrac{dy}{dx}} \\\\

\frac{dx}{dy} &= \cfrac{1}{\cfrac{dy}{dx}} \\\\

x' &= \frac{1}{y'}

\end{align}\]

This completes the explanation.

In the explanation above, the use of the chain rule assumes differentiability of

\( x = f^{-1}(y) \) without proving it, so this does not constitute a rigorous proof.

However, it is a convenient way to recall the derivative formula for inverse functions.

References:

[1] James R. Newman, THE UNIVERSAL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MATHEMATICS, George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1964

[2] 石村園子, やさしく学べる微分積分, 共立出版, December 25, 1999

[3] 難波 誠, 数学シリーズ 微分積分学, 裳華房, January 20, 2009