TABLE OF CONTENTS

・Numbers

Numbers

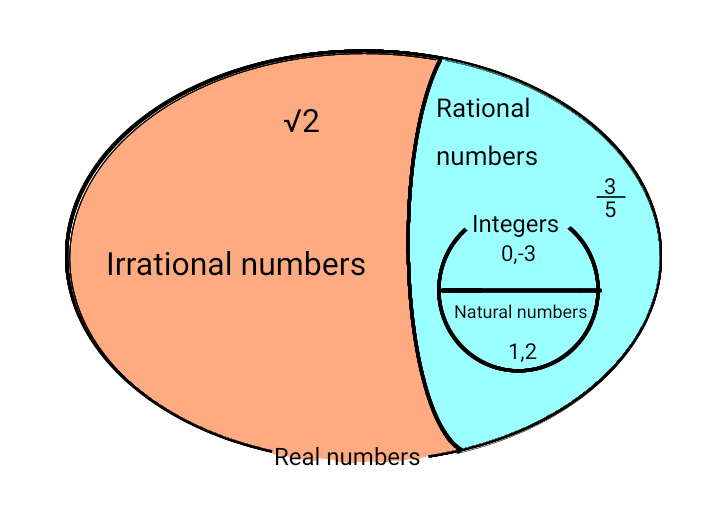

The most familiar numbers in everyday life are natural numbers. Natural numbers are

\[ 1, 2, 3, \ldots \]

These are the numbers we use for counting objects. When we add zero (\(0\)) and negative (\(-\)) versions of

natural numbers, we get integers.

For example, \(3\) is both a natural number and an integer. On the other hand, \(-3\) is an integer but not

a natural number.

In elementary school, you probably learned subtraction as taking away a natural number, like \(3\). But by

treating \(-3\) as a single number, we can also define operations like \(2 - 5\), where a smaller number is

subtracted from a larger one, allowing us to find meaningful results for such calculations.

Rational numbers consist of terminating decimals and repeating decimals.

A terminating decimal is what we commonly think of as a decimal number, such as \(0.5\) or \(0.25\).

A repeating decimal, as the name suggests, is a decimal that continues infinitely with a repeating pattern.

For example, \(0.272727\ldots\) has the digits \(2\) and \(7\) repeating endlessly.

We can also represent repeating decimals by placing a horizontal line (a vinculum) above the repeating

digits, like this:

\[ 0.272727\ldots = 0.\overline{27} \]

Any rational number can be expressed as a ratio of two integers—that is, a fraction where both the numerator and denominator are integers. For terminating decimals, we can express them as fractions by shifting the decimal point to the right until the number becomes an integer and then dividing by the corresponding power of \(10\). For example: \[ \begin{align} 0.1543 &= \frac{1543}{10 \times 10 \times 10 \times 10} \\\\ &= \frac{1543}{10000} \end{align} \] For repeating decimals, the process requires a bit more work. Let’s use \(0.123123123\ldots = 0.\dot{1}2\dot{3}\) as a concrete example to demonstrate how to convert it into a fraction.

Any rational number can be expressed as a ratio of two integers—that is, a fraction where both the numerator and denominator are integers. For terminating decimals, we can express them as fractions by shifting the decimal point to the right until the number becomes an integer and then dividing by the corresponding power of \(10\). For example: \[ \begin{align} 0.1543 &= \frac{1543}{10 \times 10 \times 10 \times 10} \\\\ &= \frac{1543}{10000} \end{align} \] For repeating decimals, the process requires a bit more work. Let’s use \(0.123123123\ldots = 0.\dot{1}2\dot{3}\) as a concrete example to demonstrate how to convert it into a fraction.

\[ \begin{align}

x &= 0.123123123 \ldots \\\\

1000x &= 123.123123 \ldots \\\\

1000x - x &= 123.123123 \ldots - 0.123123123 \ldots \\\\

999x &= 123 \\\\

x &= \frac{123}{999} = 0.123123123 \ldots

\end{align}\]

This method hinges on the calculation in the third line, where by multiplying the original repeating decimal

by \(1000\) and then subtracting the original repeating decimal, we cancel out the decimal part.

Then, in the fourth line, the remaining \(123\) on the right-hand side and the left-hand side, which is the

original repeating decimal multiplied by \(999\) (since \(1000 - 1 = 999\)), allows us to solve for \(x\).

This gives us the fraction of the original repeating decimal, which is \( \frac{123}{999} \).

Irrational numbers are infinite decimals that do not repeat. Unlike rational numbers, irrational

numbers cannot be expressed as a ratio of two integers. A familiar example of an irrational number is the

length of the diagonal of a square with side length 1, which is \( \sqrt{2} \). This is an irrational

number. The symbol \( \sqrt{} \) is called the radical sign and is read as 'square root of ...' This

number, \( \sqrt{2} \), is the value that, when multiplied by itself, gives 2, and it continues infinitely

without repeating:

\[

\sqrt{2} = 1.41421356\ldots

\]

Another number that satisfies the condition of multiplying by itself to give 2 is \( -\sqrt{2} \), which is

\[ \begin{align}

\left( - \sqrt{2} \right) \times \left( - \sqrt{2} \right) &= \left( (-1) \times \sqrt{2} \right) \times

\left( (-1) \times \sqrt{2} \right) \\\\

&= (-1) \times (-1) \times \sqrt{2} \times \sqrt{2} \\\\

&= 1 \times 2 \\\\

&= 2

\end{align}\]

With that in mind, we can think of it this way. In expressions that only involve multiplication, the order

of multiplication can be swapped. Also, remember that multiplying by \( -1 \) reverses the plus-minus sign.

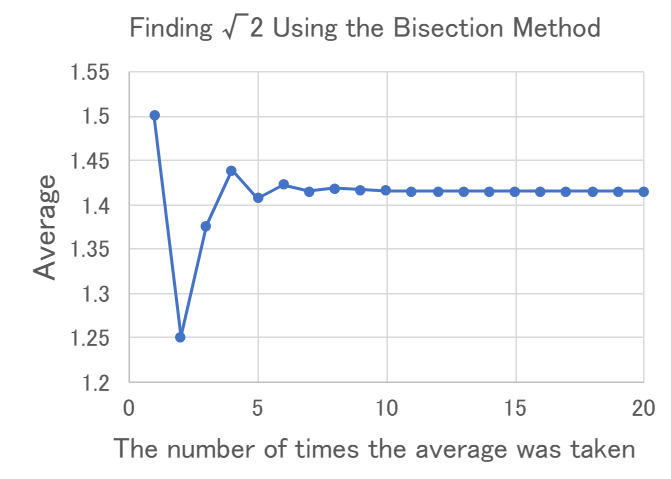

(1) \( 1 \times 1 = 1 \lt 2 \), and \( 2 \times 2 = 4 \gt 2 \), so we can infer that the number which,

when multiplied by itself, gives 2, i.e., \( \sqrt{2} \), is greater than 1 and less than 2.

(2) The average of 1 and 2 is \( (1 + 2) \div 2 = 1.5 \). Here, \( 1.5 \times 1.5 = 2.25 \gt 2 \). Therefore, we can conclude that \( \sqrt{2} \) is greater than 1 and less than 1.5.

(3) The average of 1 and 1.5 is \( (1 + 1.5) \div 2 = 1.25 \). Here, \( 1.25 \times 1.25 = 1.5625 \lt 2 \). Therefore, we can conclude that \( \sqrt{2} \) is greater than 1.25 and less than 1.5.

(4) From here on, we continue in the same manner by taking the average of two numbers. If squaring the average results in a value smaller than 2, we replace it with the smaller of the two previous numbers. If it is greater than 2, we replace it with the larger of the two previous numbers. This process is repeated.

(2) The average of 1 and 2 is \( (1 + 2) \div 2 = 1.5 \). Here, \( 1.5 \times 1.5 = 2.25 \gt 2 \). Therefore, we can conclude that \( \sqrt{2} \) is greater than 1 and less than 1.5.

(3) The average of 1 and 1.5 is \( (1 + 1.5) \div 2 = 1.25 \). Here, \( 1.25 \times 1.25 = 1.5625 \lt 2 \). Therefore, we can conclude that \( \sqrt{2} \) is greater than 1.25 and less than 1.5.

(4) From here on, we continue in the same manner by taking the average of two numbers. If squaring the average results in a value smaller than 2, we replace it with the smaller of the two previous numbers. If it is greater than 2, we replace it with the larger of the two previous numbers. This process is repeated.

The numbers we have explained so far are the main ones that appear in numerical experiments. Natural

numbers, integers, rational numbers, and irrational numbers are collectively called real numbers.

References:

[1] Wikipedia Rational number, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rational_number,

July 13, 2023

[2] James R. Newman, THE UNIVERSAL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MATHEMATICS, George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1964