TABLE OF CONTENTS

・The definition of an angle

・Trigonometric function

・Sum and difference formulas

・Composition of trigonometric functions

・Sum to product and product to sum formula

・The limit formula of the sinc function

・Note: inverse trigonometric functions

Kaya

This time, we'll be exploring trigonometric functions. Let's start with the definition of an angle.

The definition of an angle

Nayumi

An angle is just an angle, right? Like \( 180^{\circ} \) or something.

Kaya

In everyday life, angles are usually expressed in degrees (\( ^{\circ} \)), but in mathematics, we use a

method called radians to represent angles.

\[ \text{Radian measure} \]

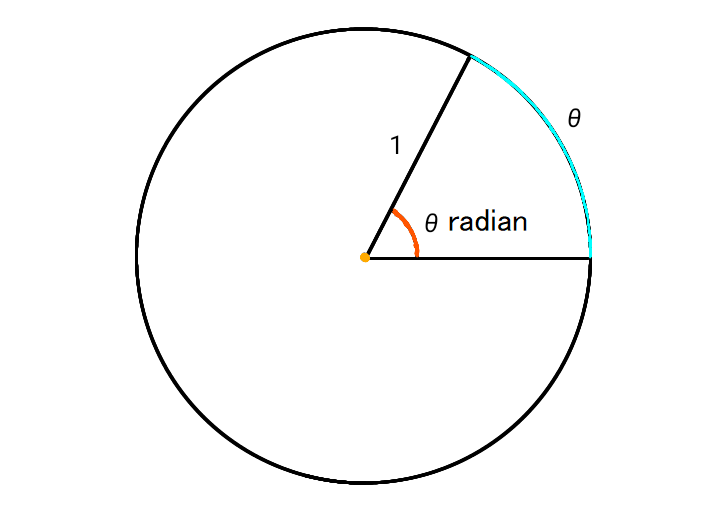

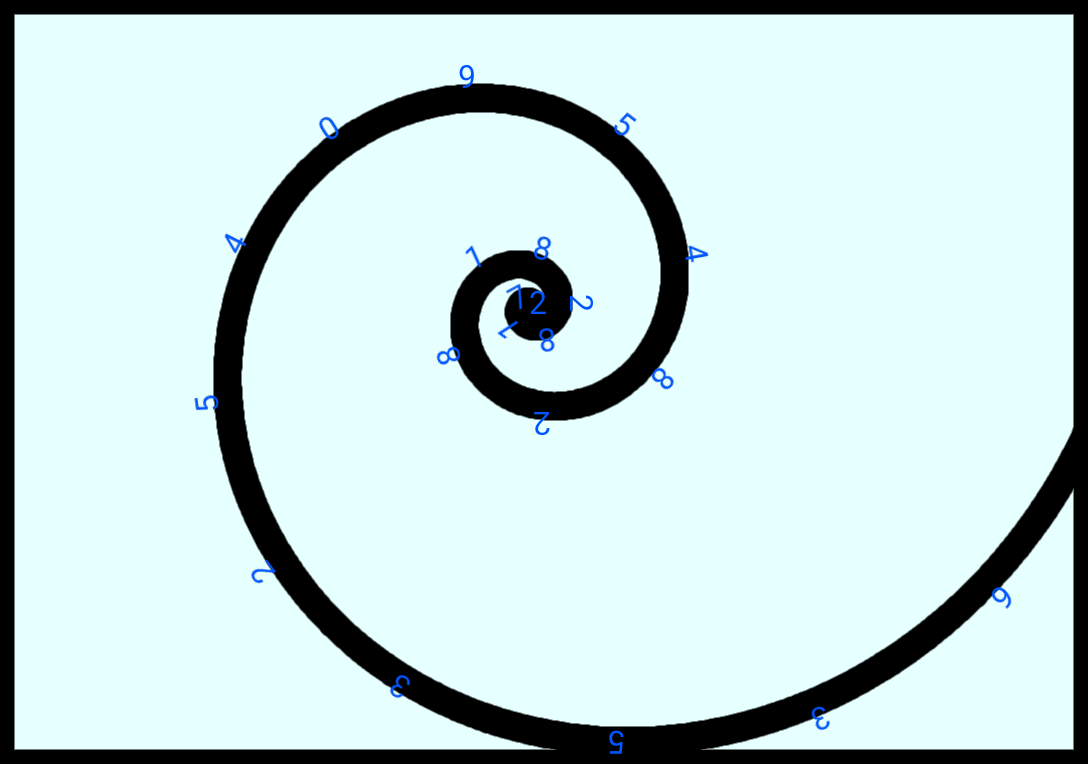

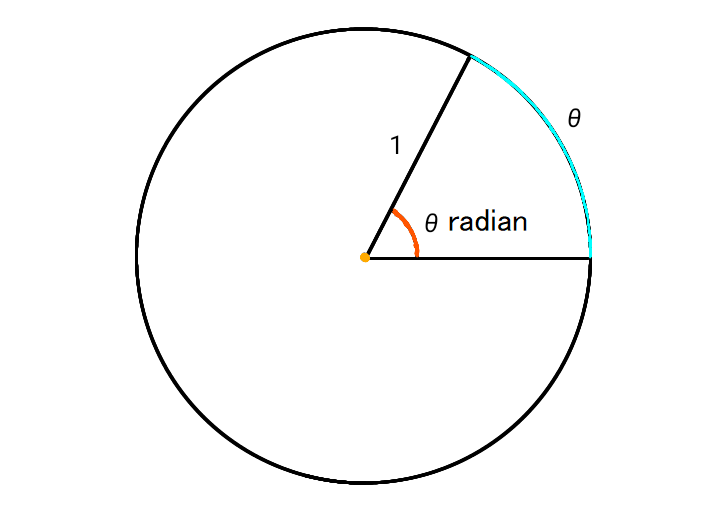

In a circle with a radius of 1, the central angle corresponding to an arc length of \(

\theta \) is called radian.

The yellow area in the diagram above represents the center of the circle. Just outside that, the orange

area shows the angle, and the outermost light blue arc represents the arc length.

Both the angle and the arc length are labeled as \( \theta \). The unit of the angle is radians, but the

unit is often omitted in practice.

There’s a fundamental relationship between radians and degrees (\( ^{\circ} \)):

\[ \pi \text{ radians} = 180^{\circ} \]

Here, \( \pi \) is the mathematical constant pi, representing the ratio of a circle's circumference

to its diameter.

Since the circumference of a circle is given by:

\[ \text{Circumference} = \text{Diameter} \times \pi, \]

a circle with radius 1 (which means the diameter is 2) has a circumference of \( 2\pi \). The angle that

spans the entire circle is \( 360^{\circ} \), so:

\[ 2\pi \text{ radians} = 360^{\circ} \]

Dividing both sides by 2 gives us the key conversion formula:

\[ \pi \text{ radians} = 180^{\circ}\]

This formula is used to convert between degrees and radians.

Nayumi

In the radian system, the arc length and the angle are directly related, aren't they?

Kaya

Exactly. Now, let’s define a general angle and extend the concept of angle to cover all real numbers.

\[ \text{General angle} \]

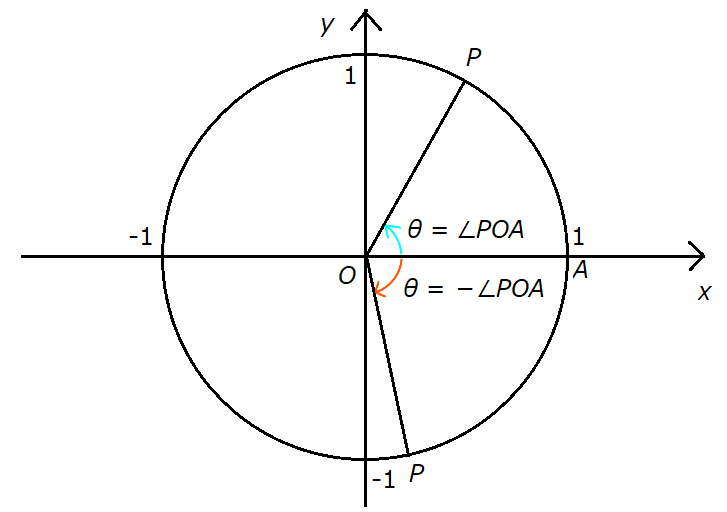

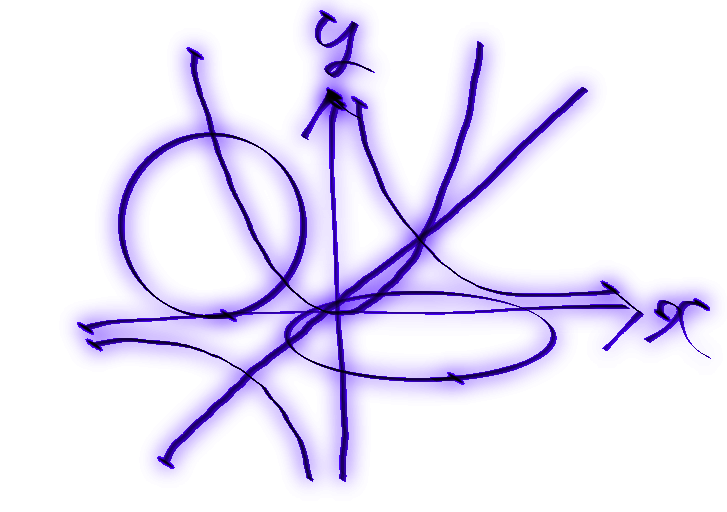

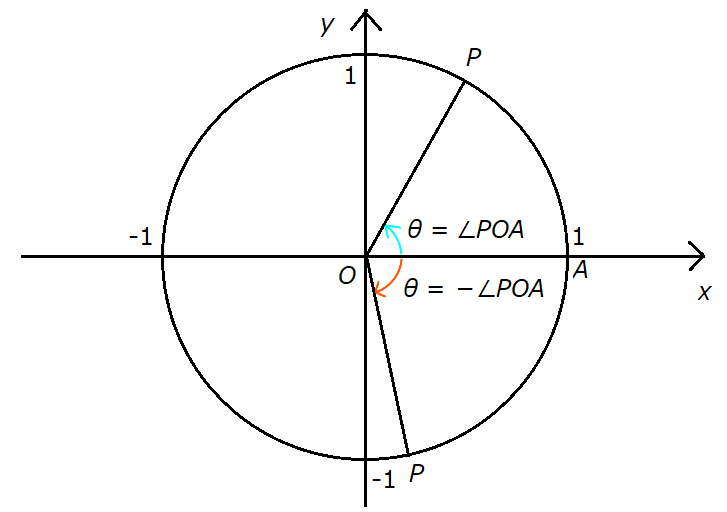

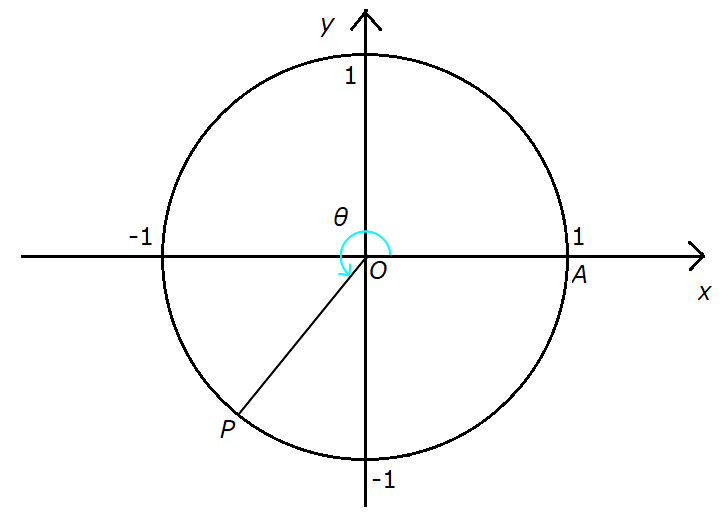

First, consider a circle with radius 1 centered at the origin \( O \) in the Cartesian plane.

This circle is called the unit circle.

Let point \( A(1,0) \) be the starting point, and suppose that point \( P \) moves along the

circumference of the unit circle.

The angle \( \theta \) is determined as follows based on the movement of point \( P \):

[1] If point \( P \) moves counterclockwise along the unit circle, define \( \theta = \angle POA

\ \ \left( 0 \leq \angle POA \lt 2 \pi \right) \).

If point \( P \) moves counterclockwise by \( n \) or more full circles, then define \( \theta = \angle

POA + 2n \pi \), where \( n \) is any natural number.

[2] If point \( P \) moves clockwise along the unit circle, define \( \theta = - \angle POA \ \

\left( 0 \leq \angle POA \lt 2 \pi \right) \). If point \( P \) moves clockwise by \( n \) or more full

circles, then define \( \theta = - \angle POA - 2n \pi \), where \( n \) is any natural number.

In the diagram above, clockwise rotation is indicated by the orange arrow, and counterclockwise rotation is

shown with the light blue arrow.

The angle \( \angle POA \) is read as “angle POA,” which refers to the angle formed by the line

segments \( OP \) and \( OA \).

A line segment is a straight line with two endpoints.

There are two regions associated with \( \angle POA \):

- the interior region enclosed by \( OP \) and \( OA \),

- and the exterior region on the opposite side.

When \( 0 \leq \theta \leq \pi \), the interior region is used to represent the general angle.

When \( \pi \lt \theta \lt 2\pi \), the exterior region is used instead.

The above diagram shows the case where the interior region is used.

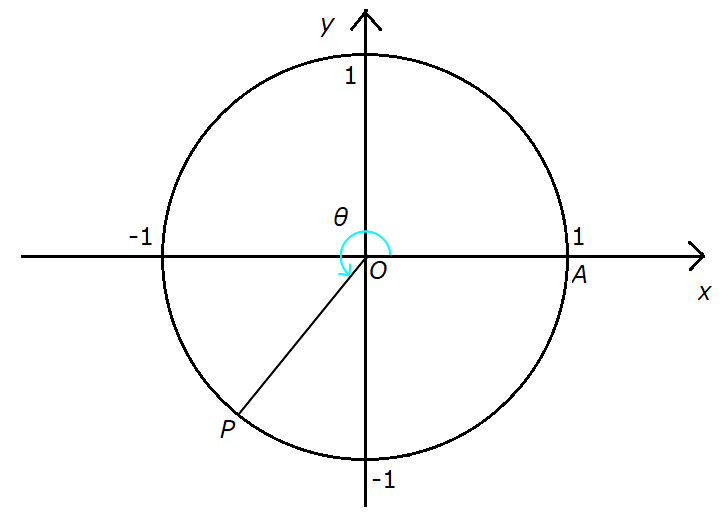

For the case where the exterior region is used, it would look like the diagram shown next.

Nayumi

Point \( P \) goes around and around, and that’s how we get a general angle, right?

Kaya

That's right. Now, let's finally move on to trigonometric functions.

Trigonometric function

Nayumi

Since they're called trigonometric functions, I guess triangles have something to do with them,

right?

Kaya

Exactly. Here's how they're defined.

\[ \text{Trigonometric function}\]

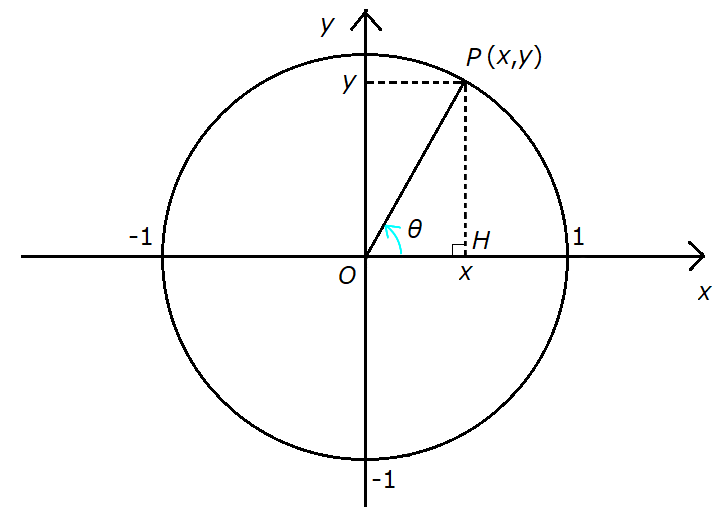

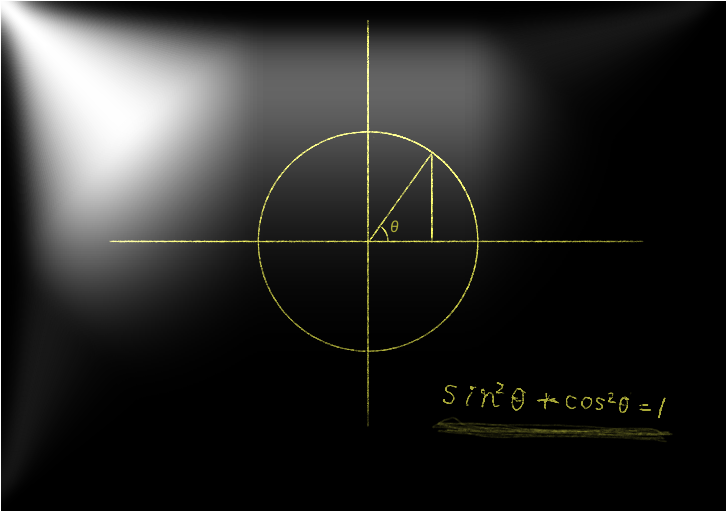

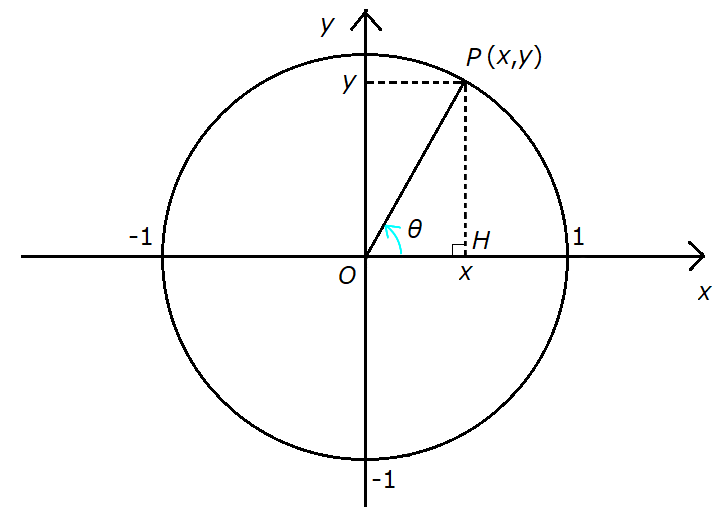

On the unit circle, take a point \( P (x,y) \) and represent the general angle as \( \theta \).

In this case, the following three functions of \( \theta \) are called trigonometric functions.

\[ \sin \theta = y\]

\[ \cos \theta = x\]

\[ \tan \theta = \frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta} = \frac{y}{x} \ (x \neq 0) \]

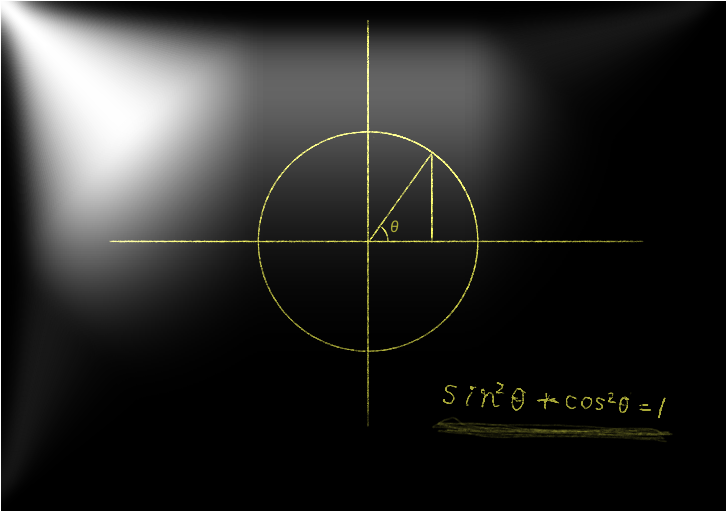

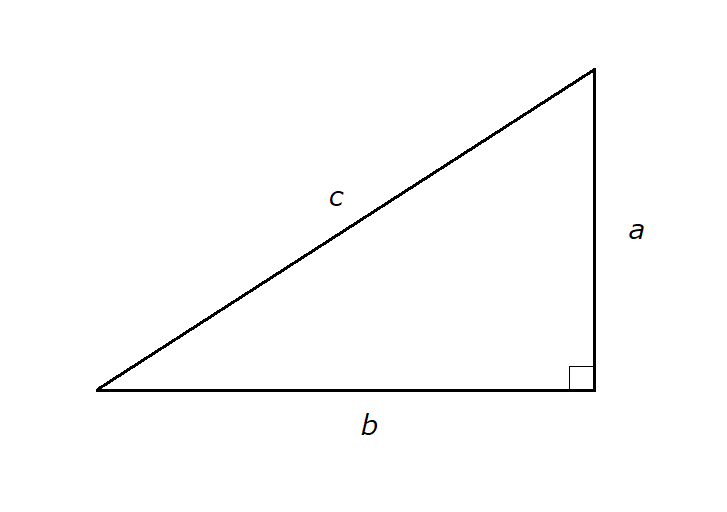

Since \( \triangle POH \) is a right triangle, we can apply the Pythagorean theorem:

Since the right triangle \( \triangle POH \) has a hypotenuse of length 1—equal to the radius of the unit

circle—and the other two sides have lengths \( \sin \theta \) and \( \cos \theta \), applying the

Pythagorean theorem gives us the following equation:

\[ \sin ^2 \theta + \cos ^2 \theta = 1 \]

※In the above formula, we use the following notation.

\[ \begin{align}

\sin ^2 \theta &= \left( \sin \theta \right) ^2 \\\\

&= \left( \sin \theta \right) \times \left( \sin \theta \right) \\\\

\cos ^2 \theta &= \left( \cos \theta \right) ^2 \\\\

&= \left( \cos \theta \right) \times \left( \cos \theta \right)

\end{align}\]

Furthermore, by dividing both sides of this equation by \( \cos ^2 \theta \), we can derive the following

formula as well.

\[ \tan ^2 \theta + 1 = \frac{1}{\cos ^2 \theta} \]

※Here, we use the following notation.

\[ \begin{align}

\tan ^2 \theta &= \left( \tan \theta \right) ^2 \\\\

&= \left( \tan \theta \right) \times \left( \tan \theta \right)

\end{align}\]

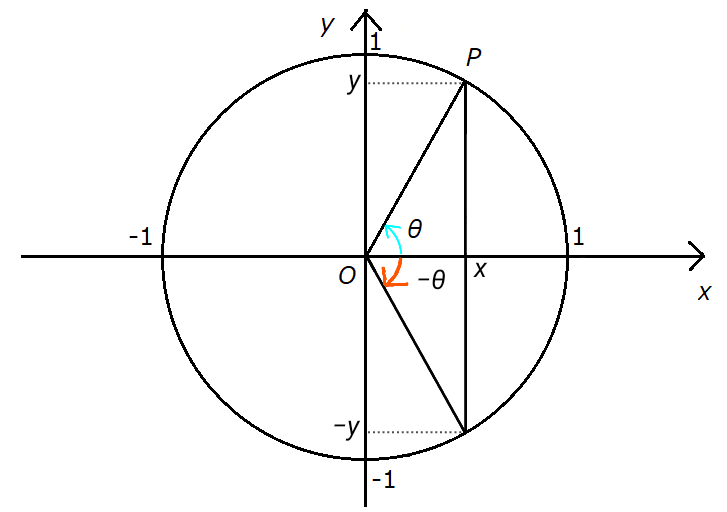

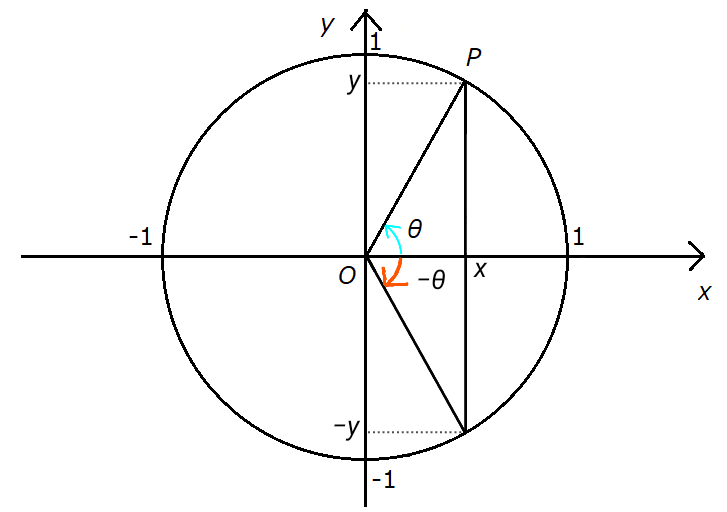

Also, the general angle \( -\theta \) is the reflection of \( \theta \) across the \( x \)-axis, so \( \sin

\theta = y \) changes sign from positive to negative. On the other hand, \( \cos \theta = x \) remains

unchanged. This can be illustrated as shown below.

Based on this property, the following identity holds.

\[ \sin (- \theta ) = - \sin \theta \]

\[ \cos (- \theta ) = \cos \theta \]

\[ \tan (- \theta ) = \frac{\sin (- \theta) }{\cos (- \theta)} = \frac{- \sin \theta }{\cos \theta} = -

\tan \theta \]

Nayumi

What are trig function graphs like?

Kaya

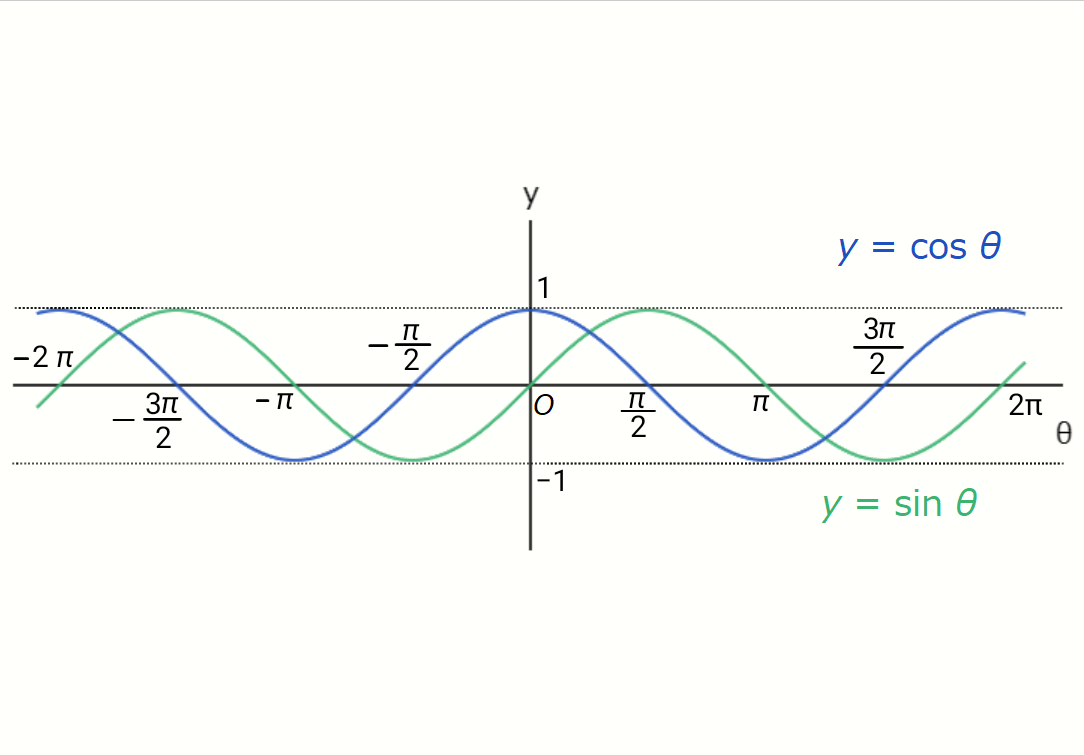

Alright. Let's start by looking at the graphs of \( \sin \theta \) and \( \cos \theta \).

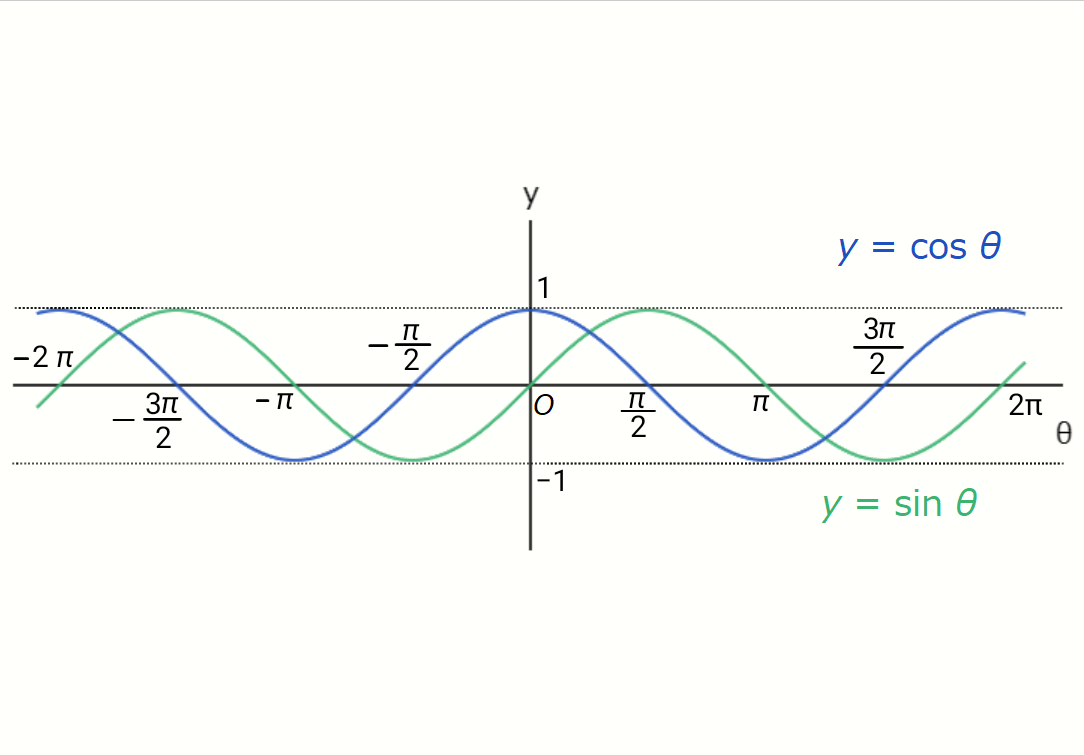

The graphs of \( y = \sin \theta \) and \( y = \cos \theta \) are called the sine wave and cosine

wave, respectively. Both of these functions are periodic functions with a period of \(

2\pi \). This is because, when a point \( P \) completes one revolution around the unit circle and returns

to its original position, the general angle \( \theta \) increases by \( 2\pi \).

Also, the maximum value of both functions is \( 1 \), and the minimum value is \( -1 \). This is because \(

\sin \theta \) and \( \cos \theta \) correspond to the coordinates of a point \( P(x, y) \) on the unit

circle, which has a radius of 1.

Moreover, as you can see from the graphs, the shapes of \( y = \sin \theta \) and \( y = \cos \theta \) are

exactly the same—they are just horizontally shifted. This relationship can be expressed with the following

equation:

\[ \sin \theta = \cos \left( \theta - \frac{\pi}{2} \right) \]

\[ \cos \theta = \sin \left( \theta + \frac{\pi}{2} \right) \]

\[ - \sin \theta = \cos \left( \theta + \frac{\pi}{2} \right) \]

\[ - \cos \theta = \sin \left( \theta - \frac{\pi}{2} \right) \]

Kaya

There are other things we can observe from these graphs, but let's leave \( \sin \) and \( \cos \) for

now and move on to the graph of \( \tan \).

Nayumi

What does the graph of \( \tan \) look like?

Kaya

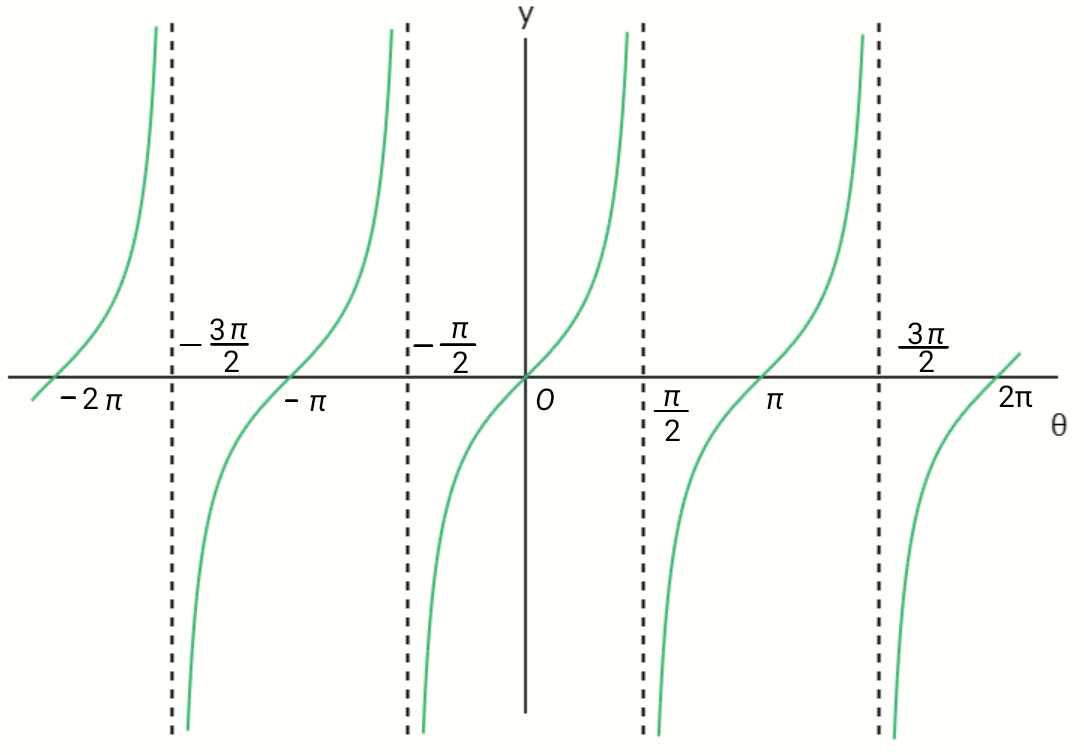

This is it.

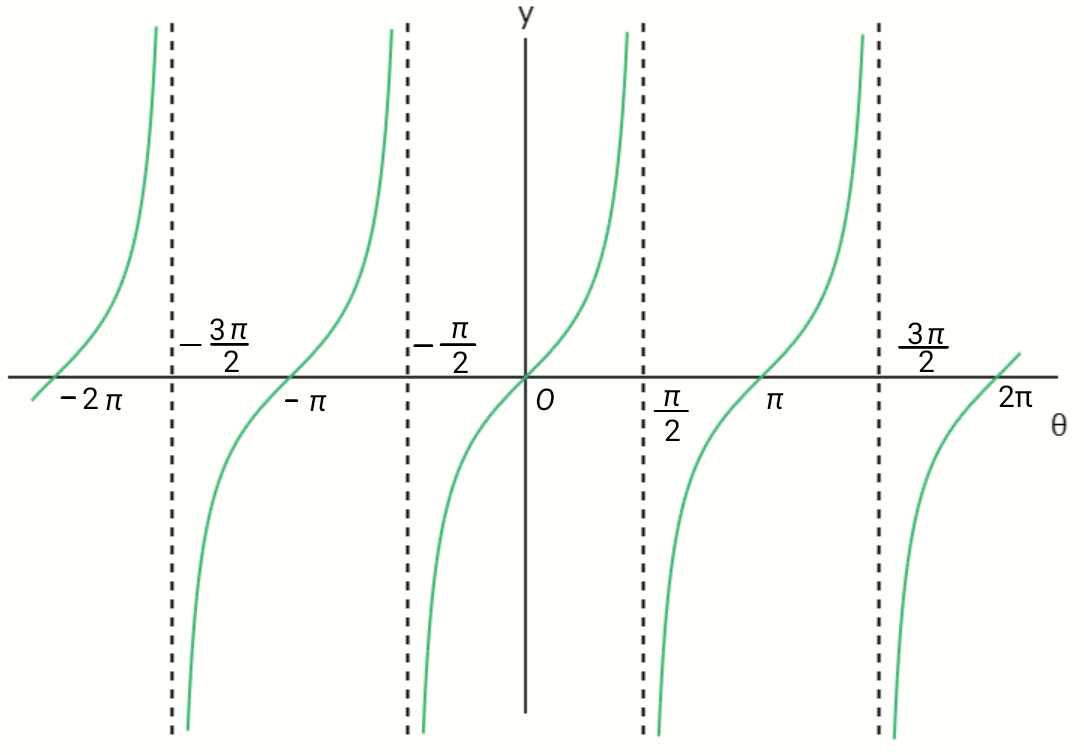

The function \( y = \tan \theta \) is a periodic function with a period of \( \pi \). Additionally, the

vertical asymptotes occur at \( x = \pm \frac{2n + 1}{2} \pi \ \ (n = 0,1,2, \ldots) \), and \( \tan \theta

\) is undefined at these values of \( x \).

Nayumi

It’s starting to look like a frame-by-frame film.

Kaya

Since the asymptotes are vertical lines. Let’s stop here with the trigonometric function graphs and move

on to explaining the sum and difference formulas.

Sum and difference formulas

\[ \text{Sum and difference formulas} \]

Let \( \alpha \) and \( \beta \) be general angles. Then, the following identities hold.

\[ \sin ( \alpha + \beta ) = \sin \alpha \cos \beta + \cos \alpha \sin \beta \]

\[ \sin ( \alpha - \beta ) = \sin \alpha \cos \beta - \cos \alpha \sin \beta \]

\[ \cos ( \alpha + \beta ) = \cos \alpha \cos \beta - \sin \alpha \sin \beta \]

\[ \cos ( \alpha - \beta ) = \cos \alpha \cos \beta + \sin \alpha \sin \beta \]

\[ \tan ( \alpha + \beta ) = \frac{\tan \alpha + \tan \beta}{1 - \tan \alpha \tan \beta} \]

\[ \tan ( \alpha - \beta ) = \frac{\tan \alpha - \tan \beta}{1 + \tan \alpha \tan \beta} \]

Nayumi

We’re diving into a formula fest now.

Kaya

The proof’s a little tricky, but it’s such a handy theorem, so let’s go over it.

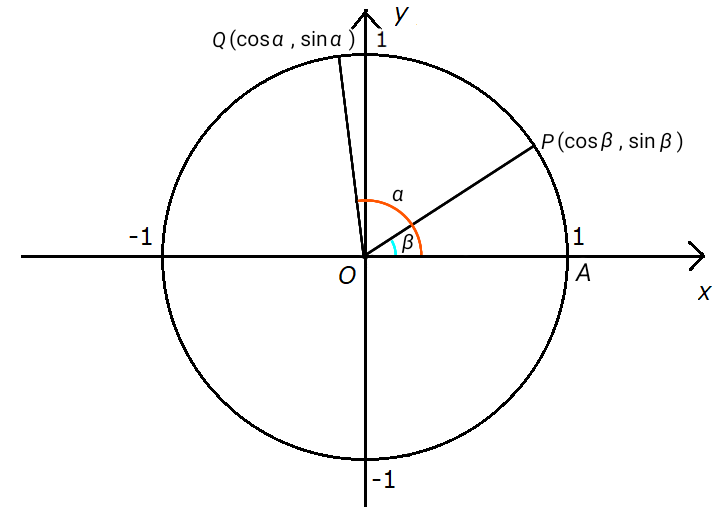

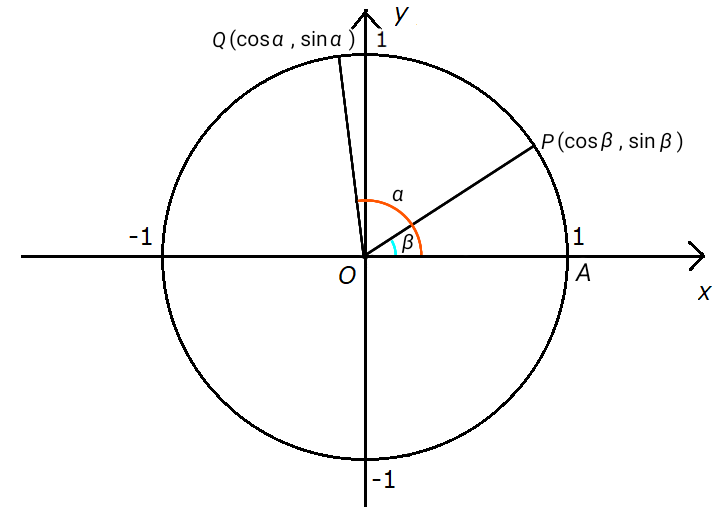

First, let’s take two points on the unit circle: \( P (\cos \beta , \sin \beta) \) and \( Q (\cos \alpha ,

\sin \alpha ) \).

Here, let \( \angle POA = \beta \) and \( \angle QOA = \alpha \).

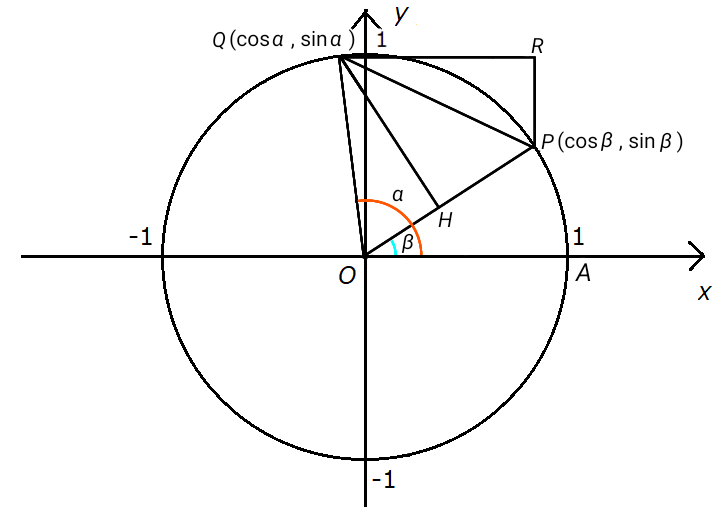

Next, consider triangle \( OPQ \), and draw a perpendicular line \( QH \) from point \( Q \) to the side \(

OP \).

Here, since \( \angle QOP = \alpha - \beta \), if we treat the line \( OP \) as the \( x \)-axis, we can see

that:

\[ QH = \sin(\alpha - \beta) \]

\[ OH = \cos(\alpha - \beta) \]

It might be easier to understand if you tilt your head to the left so that line \( OP \) appears horizontal.

Also, since

\[

\begin{align}

HP &= OP - OH \\\\

&= 1 - \cos (\alpha - \beta)

\end{align}

\]

holds, we can apply the Pythagorean theorem to triangle \( QHP \) to obtain the following equation.

\[ \begin{align}

PQ^2 &= QH^2 + HP^2 \\\\

&= \sin ^2 (\alpha - \beta ) + (1 - \cos (\alpha - \beta) )^2 \\\\

&= \sin ^2 (\alpha - \beta ) + 1 - 2 \cos (\alpha - \beta) + \cos ^2 (\alpha - \beta) \\\\

&= \left\{ \sin ^2 (\alpha - \beta ) + \cos ^2 (\alpha - \beta) \right\} + 1 - 2 \cos (\alpha - \beta)

\\\\

&= 2 - 2 \cos (\alpha - \beta)

\end{align} \]

The expression \( \sin^2(\alpha - \beta) + \cos^2(\alpha - \beta) \) equals 1, based on the identity we

derived earlier from the Pythagorean theorem:

\[ \sin^2 \theta + \cos^2 \theta = 1 \]

Also, the term \( (1 - \cos(\alpha - \beta))^2 \) is calculated using the following multiplication formula.

\[ \text{Multiplication formula}\]

\[ (a + b)^2 = a^2 + 2ab + b^2 \]

This formula can be derived by repeatedly applying the distributive property, as shown below.

\[ \begin{align}

(a + b)^2 &= (a + b) (a + b) \\\\

&= (a + b) a + (a + b) b \\\\

&= a^2 + ab + ab + b^2 \\\\

&= a^2 + 2ab + b^2

\end{align}\]

Nayumi

I’m barely keeping up.

Kaya

Alright. Now, let’s continue and find \( PQ^2 \) by forming another triangle.

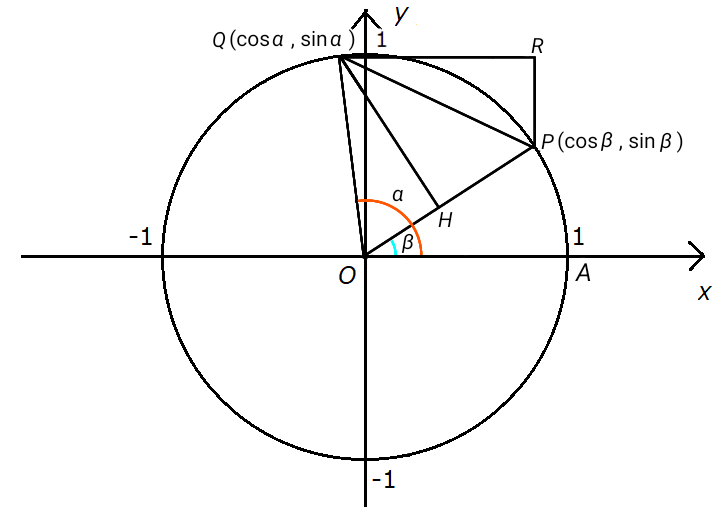

Let the intersection of \( x = \cos \beta \) and \( y = \sin \alpha \) be denoted as \( R \).

By applying the Pythagorean theorem to the triangle \( PQR \), we can find \( PQ^2 \) in a different form

from before.

\[ \begin{align}

PQ^2 &= RP^2 + QR^2 \\\\

&= \left( \sin \alpha - \sin \beta \right) ^2 + \left( \cos \alpha - \cos \beta \right) ^2 \\\\

&= \sin ^2 \alpha - 2 \sin \alpha \sin \beta + \sin ^2 \beta + \cos ^2 \alpha - 2 \cos \alpha \cos \beta

+ \cos ^2 \beta \\\\

&= 2 - 2 \left( \sin \alpha \sin \beta + \cos \alpha \cos \beta \right)

\end{align} \]

Thus, we have found \( PQ^2 \) in two different ways. Since the values obtained by both methods for \( PQ^2

\) are the same, these must be equal.

Therefore, the following equation holds, and one of the addition formulas is derived.

\[ \begin{align}

2 - 2 \cos (\alpha - \beta) &= 2 - 2 \left( \sin \alpha \sin \beta + \cos \alpha \cos \beta \right) \\\\

\cos (\alpha - \beta) &= \sin \alpha \sin \beta + \cos \alpha \cos \beta

\end{align}\]

Nayumi

I feel a sense of accomplishment. But we’ve only got one so far...

Kaya

Don’t worry, it’ll go faster from here, so you don’t have to be too concerned.

Nayumi

Really?

Kaya

Yeah. First, let’s substitute \( \beta = - \beta \) into the formula for \( \cos (\alpha - \beta) \) we

derived earlier and manipulate the equation.

\[ \begin{align}

\cos (\alpha - (- \beta ) ) &= \cos \alpha \cos ( - \beta ) + \sin \alpha \sin (- \beta ) \\\\

\cos (\alpha + \beta ) &= \cos \alpha \cos \beta - \sin \alpha \sin \beta

\end{align} \]

Here, we used the following formulas.

\[ \sin (- \beta ) = - \sin \beta \]

\[ \cos (- \beta ) = \cos \beta \]

Nayumi

So, with that, we’ve got the addition formula for \( \cos (\alpha + \beta ) \), huh.

Kaya

Yep. Pretty fast, right? Next, let’s substitute \[ \beta = \beta + \frac{\pi}{2} \] into the formula for

\( \cos (\alpha + \beta ) \) we just derived and manipulate the equation.

\[ \begin{align}

\cos \left( \alpha + \left( \beta + \frac{\pi}{2} \right) \right) &= \cos \alpha \cos \left( \beta +

\frac{\pi}{2} \right) - \sin \alpha \sin \left( \beta + \frac{\pi}{2} \right) \\\\

\cos \left( ( \alpha + \beta ) + \frac{\pi}{2} \right) &= \cos \alpha (- \sin \beta ) - \sin \alpha \cos

\beta \\\\

- \sin ( \alpha + \beta ) &= - \cos \alpha \sin \beta - \sin \alpha \cos \beta \\\\

\sin ( \alpha + \beta ) &= \sin \alpha \cos \beta + \cos \alpha \sin \beta

\end{align} \]

Here, we used the following formulas.

\[ \sin \left( \theta + \frac{\pi}{2} \right) = \cos \theta \]

\[ \cos \left( \theta + \frac{\pi}{2} \right) = - \sin \theta \]

Kaya

With this, we’ve found the addition formula for \( \sin ( \alpha + \beta ) \). Now, let’s substitute \(

\beta = - \beta \) into it.

\[ \begin{align}

\sin (\alpha + (- \beta ) ) &= \sin \alpha \cos ( - \beta ) + \cos \alpha \sin (- \beta ) \\\\

\sin (\alpha - \beta ) &= \sin \alpha \cos \beta - \cos \alpha \sin \beta

\end{align} \]

Nayumi

We’ve found the formula for \( \sin (\alpha - \beta ) \), right?

Kaya

Yeah. Now we’ve got the addition formulas for both \( \sin \) and \( \cos \).

Nayumi

The remaining one is for \( \tan \).

Kaya

The addition formula for \( \tan \) can be derived from the addition formulas for \( \sin \) and \( \cos

\). Let’s start with \( \tan (\alpha + \beta) \).

\[ \begin{align}

\tan (\alpha + \beta) &= \frac{\sin (\alpha + \beta)}{\cos (\alpha + \beta)} \\\\

&= \frac{\sin \alpha \cos \beta + \cos \alpha \sin \beta}{\cos \alpha \cos \beta - \sin \alpha \sin

\beta} \\\\

&= \frac{\tan \alpha + \tan \beta}{1 - \tan \alpha \tan \beta}

\end{align} \]

From the second line to the third line, we divided both the numerator and denominator by \( \cos \alpha \cos

\beta \).

Nayumi

I see, it works out pretty nicely.

Kaya

Yeah. And \( \tan (\alpha - \beta) \) can be obtained by substituting \( \beta = - \beta \) into the

formula for \( \tan (\alpha + \beta) \).

\[ \begin{align}

\tan (\alpha + (- \beta)) &= \frac{\tan \alpha + \tan (- \beta)}{1 - \tan \alpha \tan (- \beta) } \\\\

\tan (\alpha - \beta ) &= \frac{\tan \alpha - \tan \beta}{1 + \tan \alpha \tan \beta }

\end{align} \]

Here, we used the following formula.

\[ \tan ( - \beta ) = - \tan \beta \]

Kaya

With this, we’ve derived the addition formulas for \( \sin \), \( \cos \), and \( \tan \).

Nayumi

It was long, but once we got one, the rest just followed easily.

Kaya

Exactly. Now, let’s move on and introduce the trigonometric identities for the composition that can be

derived from the addition formulas.

Composition of trigonometric functions

\[ \text{Composition of trigonometric functions} \]

\[ a \sin \theta + b \cos \theta = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2} \sin \left( \theta + \alpha \right) \]

Here,

\[ \begin{align}

\cos \alpha &= \frac{a}{\sqrt{a^2 + b^2}} \\\\

\sin \alpha &= \frac{b}{\sqrt{a^2 + b^2}}

\end{align}\]

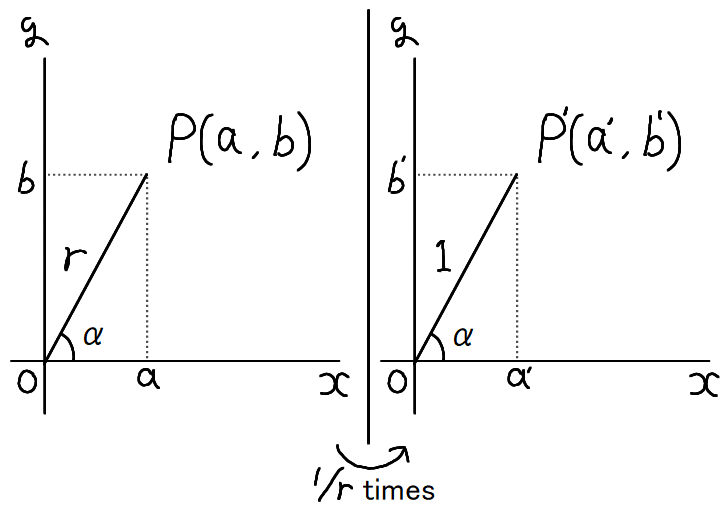

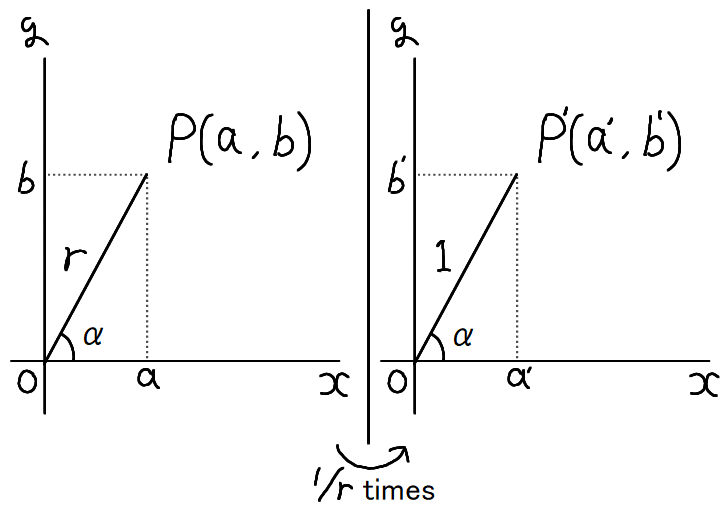

To derive this formula, we first place point \( a \) on the \( x \)-axis and point \( b \) on the \( y

\)-axis, as shown on the left side of the diagram.

Then, for the point \( P \left( a, b \right) \), by the Pythagorean theorem, we have

\[ \begin{align}

OP = r = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2}

\end{align}\]

Next, we scale the left side of the diagram by \( 1/r \) in both the \( x \)- and \( y \)-directions.

This is shown on the right side of the diagram, where we have

\[ \begin{align}

a' &= \frac{a}{r} = \cos \alpha \\\\

b' &= \frac{b}{r} = \sin \alpha

\end{align}\]

Thus, we can conclude that

\[ \begin{align}

a \sin \theta + b \cos \theta &= r \cos \alpha \sin \theta + r \sin \alpha \cos \theta \\\\

&= r \left( \cos \alpha \sin \theta + \sin \alpha \cos \theta \right) \\\\

&= r \sin \left( \theta + \alpha \right)

\end{align}\]

Therefore, we have proven the trigonometric identity for the composition.

Nayumi

So, the sine and cosine of the same angle can be combined into a single sine, huh?

Kaya

Exactly. Now, let’s move on and introduce the sum and product identities that can be derived from the

addition formulas.

Sum to product and product to sum formula

Nayumi

So, these can be derived from the addition formulas.

Kaya

Yep. First, let’s introduce the formula that transforms a product into a sum.

\[ \text{Product to sum formula} \]

\[ \begin{align}

\sin \alpha \cos \beta &= \frac{1}{2} \left\{ \sin (\alpha + \beta) + \sin (\alpha - \beta) \right\}

\\\\

\cos \alpha \sin \beta &= \frac{1}{2} \left\{ \sin (\alpha + \beta) - \sin (\alpha - \beta) \right\}

\\\\

\cos \alpha \cos \beta &= \frac{1}{2} \left\{ \cos (\alpha + \beta) + \cos (\alpha - \beta) \right\}

\\\\

\sin \alpha \sin \beta &= - \frac{1}{2} \left\{ \cos (\alpha + \beta) - \cos (\alpha - \beta) \right\}

\\\\

\end{align}\]

Nayumi

There are four types of combinations of \( \sin \) and \( \cos \), huh?

Kaya

Yep. Let’s derive them one by one, starting from the first equation.

By adding both sides of the following equations:

\[ \begin{align}

\sin ( \alpha + \beta ) &= \sin \alpha \cos \beta + \cos \alpha \sin \beta \\

\sin (\alpha - \beta ) &= \sin \alpha \cos \beta - \cos \alpha \sin \beta \\

\end{align}\]

we get

\[ \sin ( \alpha + \beta ) + \sin (\alpha - \beta ) = 2 \sin \alpha \cos \beta \]

Then, by dividing both sides by 2 and swapping the left and right sides, we obtain

\[ \sin \alpha \cos \beta = \frac{1}{2} \left\{ \sin (\alpha + \beta) + \sin (\alpha - \beta) \right\}

\]

Nayumi

It’s surprisingly simple.

Kaya

Well, yeah. For the second-to-last equation, we just subtract both sides like this.

By subtracting both sides of the following equations:

\[ \begin{align}

\sin ( \alpha + \beta ) &= \sin \alpha \cos \beta + \cos \alpha \sin \beta \\

\sin (\alpha - \beta ) &= \sin \alpha \cos \beta - \cos \alpha \sin \beta \\

\end{align}\]

we get

\[ \sin ( \alpha + \beta ) - \sin (\alpha - \beta ) = 2 \cos \alpha \sin \beta \]

Then, by dividing both sides by 2 and swapping the left and right sides, we obtain

\[ \cos \alpha \sin \beta = \frac{1}{2} \left\{ \sin (\alpha + \beta) - \sin (\alpha - \beta) \right\}

\]

Nayumi

Almost the same.

Kaya

For the third equation, we add both sides of the \( \cos \) addition formula.

By adding both sides of the following equations:

\[ \begin{align}

\cos ( \alpha + \beta ) &= \cos \alpha \cos \beta - \sin \alpha \sin \beta \\

\cos (\alpha - \beta ) &= \cos \alpha \cos \beta + \sin \alpha \sin \beta \\

\end{align}\]

we get

\[ \cos ( \alpha + \beta ) + \cos (\alpha - \beta ) = 2 \cos \alpha \cos \beta \]

Then, by dividing both sides by 2 and swapping the left and right sides, we obtain

\[ \cos \alpha \cos \beta = \frac{1}{2} \left\{ \cos (\alpha + \beta) + \cos (\alpha - \beta) \right\}

\]

Nayumi

It’s all about \( \cos \), huh?

Kaya

Yeah. For the last equation, we subtract both sides of the \( \cos \) addition formula.

By subtracting both sides of the following equations:

\[ \begin{align}

\cos ( \alpha + \beta ) &= \cos \alpha \cos \beta - \sin \alpha \sin \beta \\

\cos (\alpha - \beta ) &= \cos \alpha \cos \beta + \sin \alpha \sin \beta \\

\end{align}\]

we get

\[ \cos ( \alpha + \beta ) - \cos (\alpha - \beta ) = - 2 \sin \alpha \sin \beta \]

Then, by dividing both sides by -2 and swapping the left and right sides, we obtain

\[ \sin \alpha \sin \beta = - \frac{1}{2} \left\{ \cos (\alpha + \beta) - \cos (\alpha - \beta) \right\}

\]

Nayumi

Among the four formulas, this is the only one where the \( -\frac{1}{2} \) appears outside the curly

brackets on the right-hand side.

Kaya

Yeah. Now that we’ve derived all the formulas for converting a product into a sum, let’s move on to the

formulas for converting a sum into a product.

\[ \text{Sum to product formula} \]

\[ \begin{align}

\sin A + \sin B &= 2 \sin \frac{A+B}{2} \cos \frac{A-B}{2} \\\\

\sin A - \sin B &= 2 \cos \frac{A+B}{2} \sin \frac{A-B}{2} \\\\

\cos A + \cos B &= 2 \cos \frac{A+B}{2} \cos \frac{A-B}{2} \\\\

\cos A - \cos B &= - 2 \sin \frac{A+B}{2} \sin \frac{A-B}{2}

\end{align}\]

Nayumi

So, there are four types here as well.

Kaya

To derive the sum to product formulas, we can simply apply a variable substitution to the product to sum

formulas.

In the product to sum formulas,

let

\[ \alpha + \beta = A \]

\[ \alpha - \beta = B \]

If we add these two equations, we get

\[ \alpha = \frac{A+B}{2} \]

and if we subtract them, we get

\[ \beta = \frac{A-B}{2} \]

By substituting these into the product to sum formulas, we can derive the sum to product formulas.

Nayumi

Hmm, I got it right away.

Kaya

It looks complicated, but once you try it, it’s not so bad, right?

Nayumi

Yeah. Still, I wonder when I’ll actually use these formulas.

Kaya

You’ll use them eventually, so don’t worry about it.

Nayumi

It’s not like I’m worried or anything.

Kaya

Is that so? Well then, let’s wrap things up by explaining a famous limit formula involving the sinc

function.

The limit formula of the sinc function

Nayumi

What's the sinc function?

Kaya

The definition of the sinc function is this.

\[ {\rm {sinc}} \ x = \frac{\sin x}{x} \]

Nayumi

So it’s \( \sin x \) divided by \( x \).

Kaya

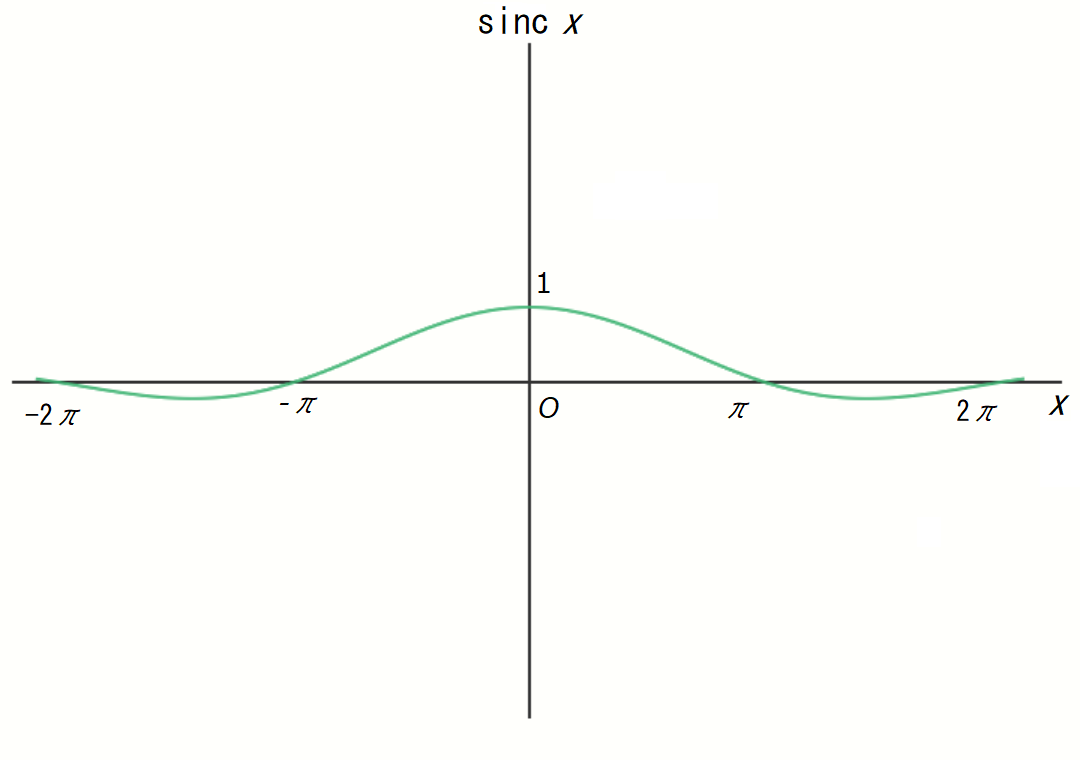

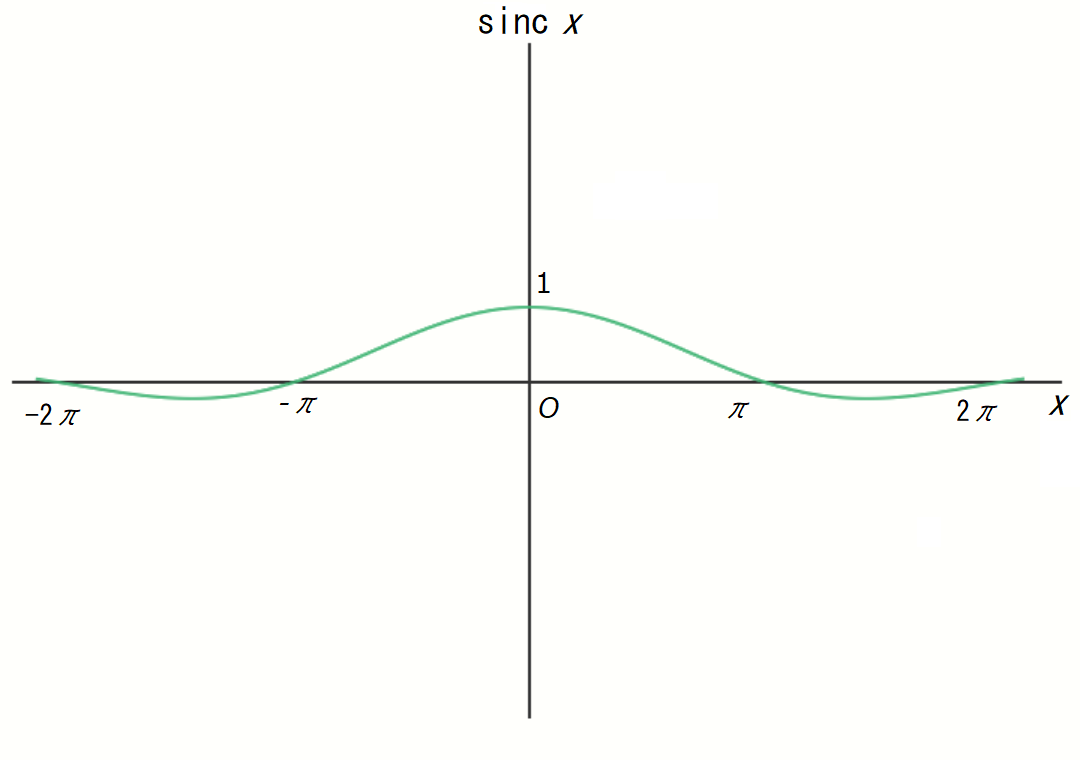

Exactly. And this is what the graph of the function looks like.

Nayumi

It looks like a mountain.

Kaya

Yeah, you could say that. And here’s the famous limit formula related to this function.

\[ \lim _{x \to 0} \frac{\sin x}{x} = 1 \]

The important point about this formula is that although both the numerator and denominator of the sinc

function become \(0\) at \(x = 0\), the sinc function still has a well-defined limit.

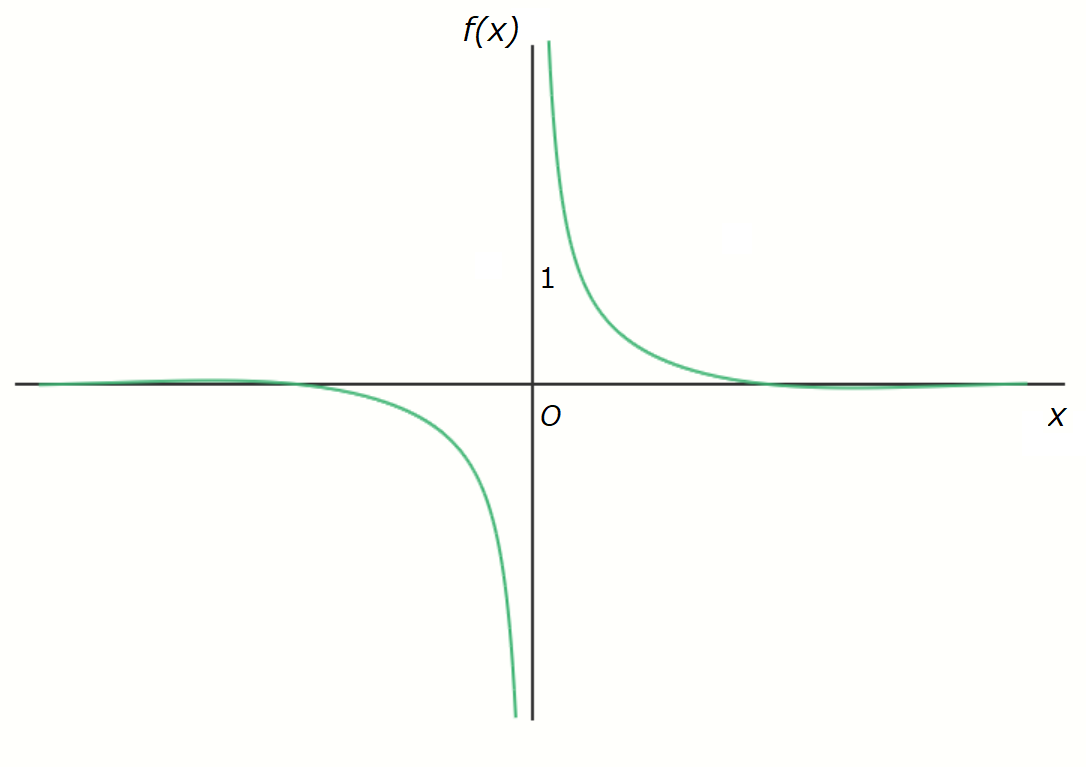

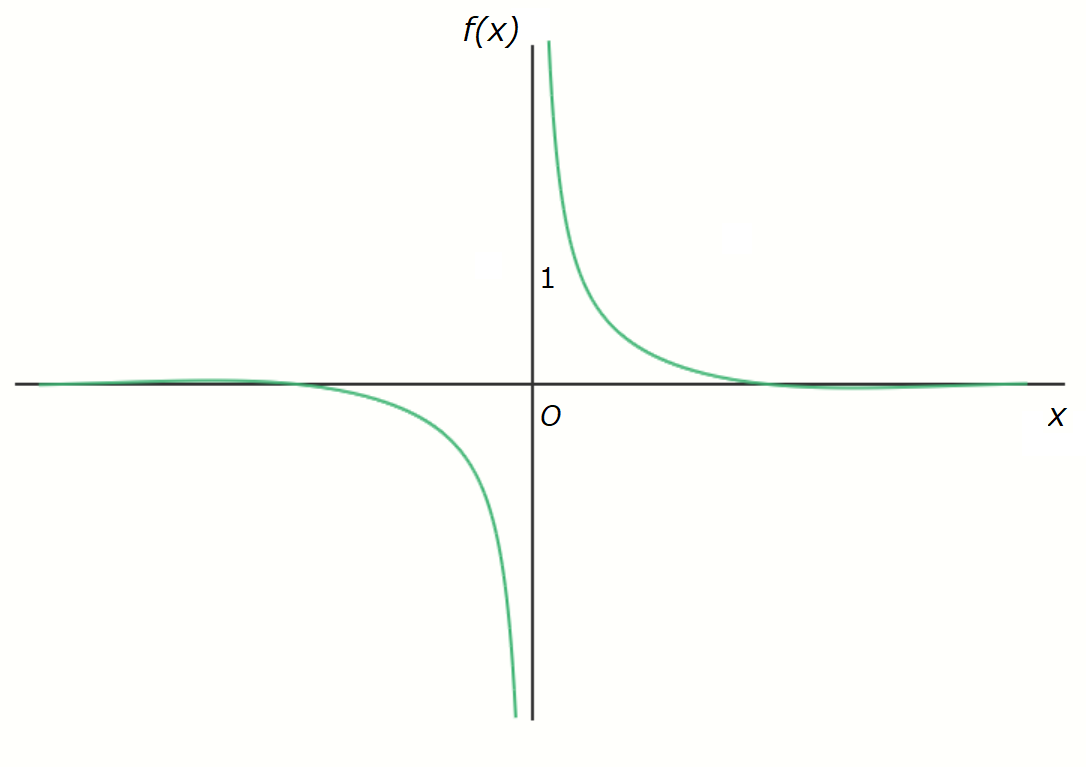

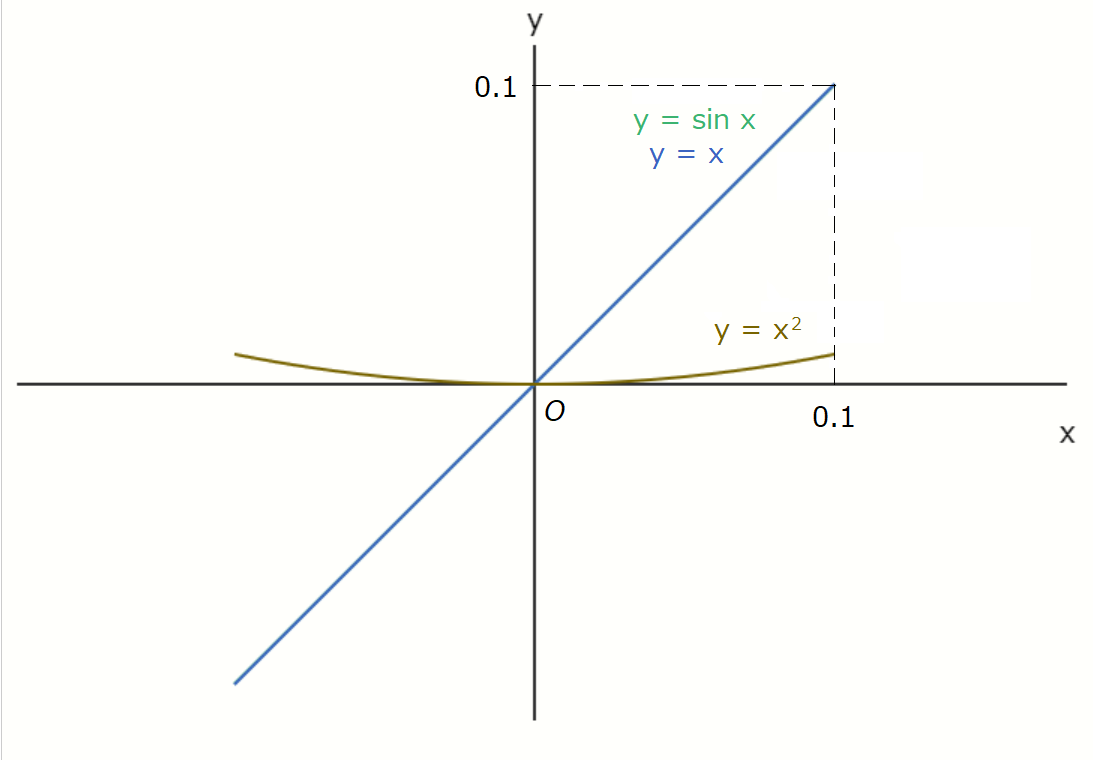

This isn't a simple matter of saying \(0 \div 0 = 1\); for example, if you replace the denominator of the

sinc function with \(x^2\) and plot the graph of the resulting function, you can see that it doesn't seem to

converge to \(1\) as \(x\) approaches \(0\).

However, it’s still true that for this function as well, both the numerator and denominator become \(0\) at

\(x = 0\).

\[ f(x) = \frac{\sin x}{x^2} \]

To put it simply, the difference is that near \(x = 0\), you can treat \(\sin x\) as essentially the same

as \(x\) without any problem.

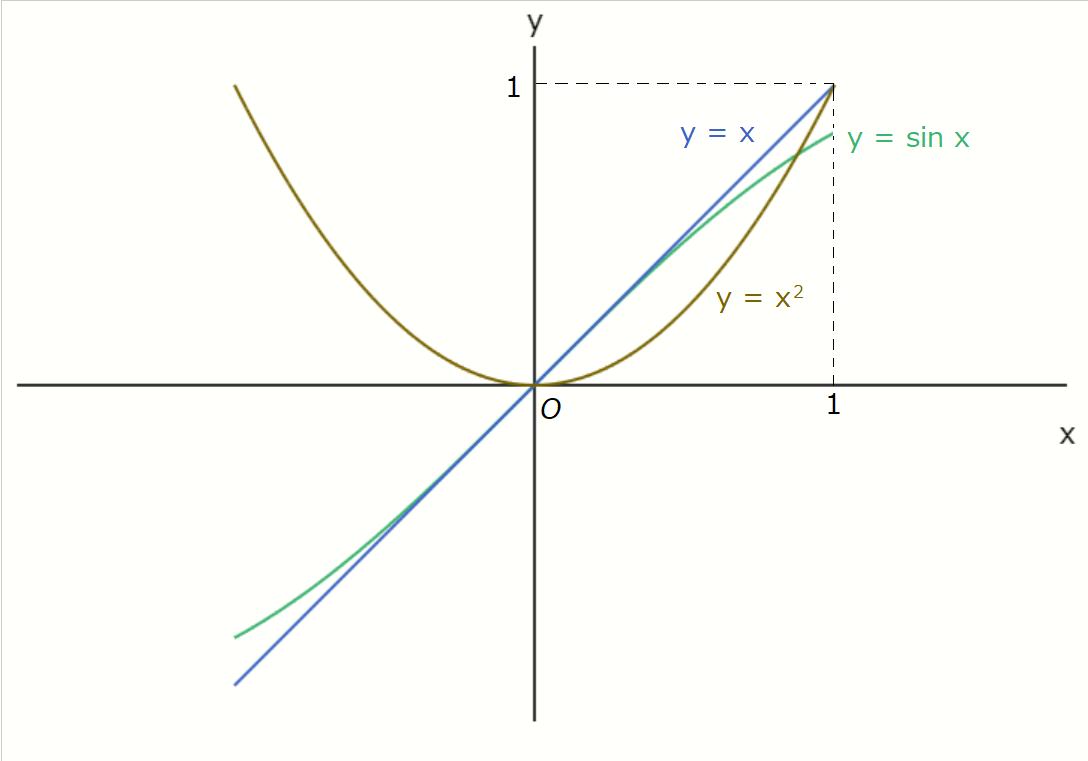

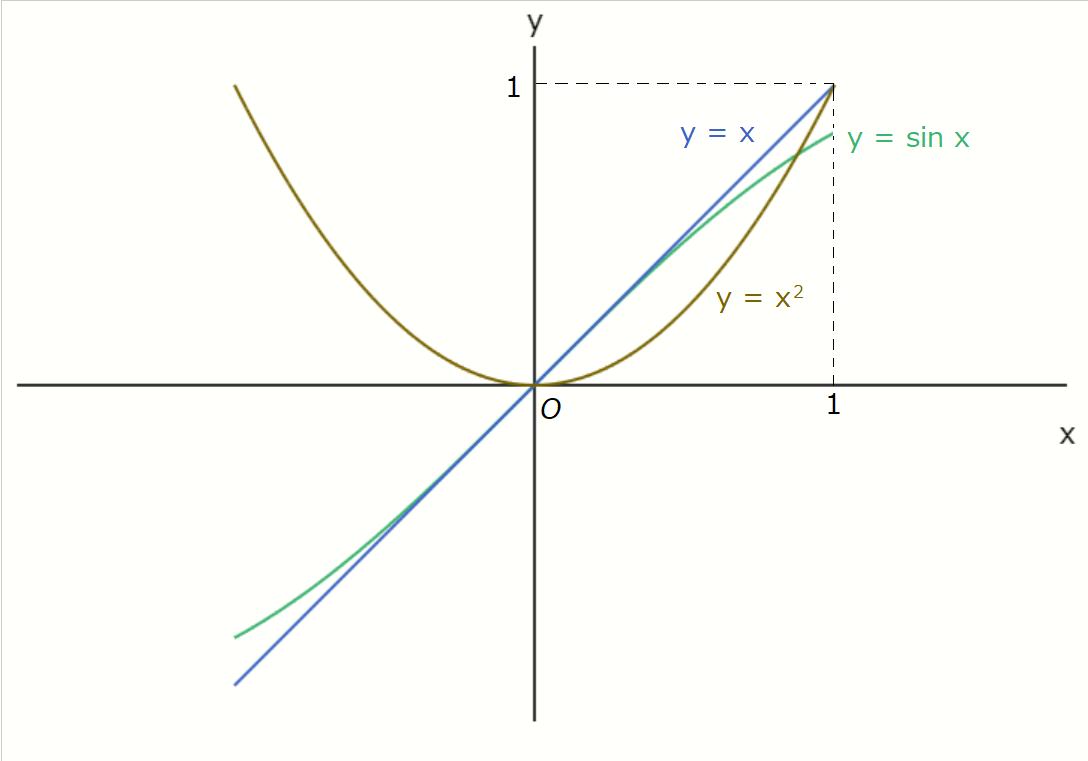

For comparison, let's take a look at the graphs of \(\sin x\), \(x\), and \(x^2\) near \(x = 0\).

Nayumi

Hmm, it looks like after passing about \( x = \frac{1}{2} \), you can't really tell the difference

between \( \sin x \) and \( x \) anymore.

But when you're super close to \( x=0 \), all three graphs are at \( y=0 \) and completely

indistinguishable.

Kaya

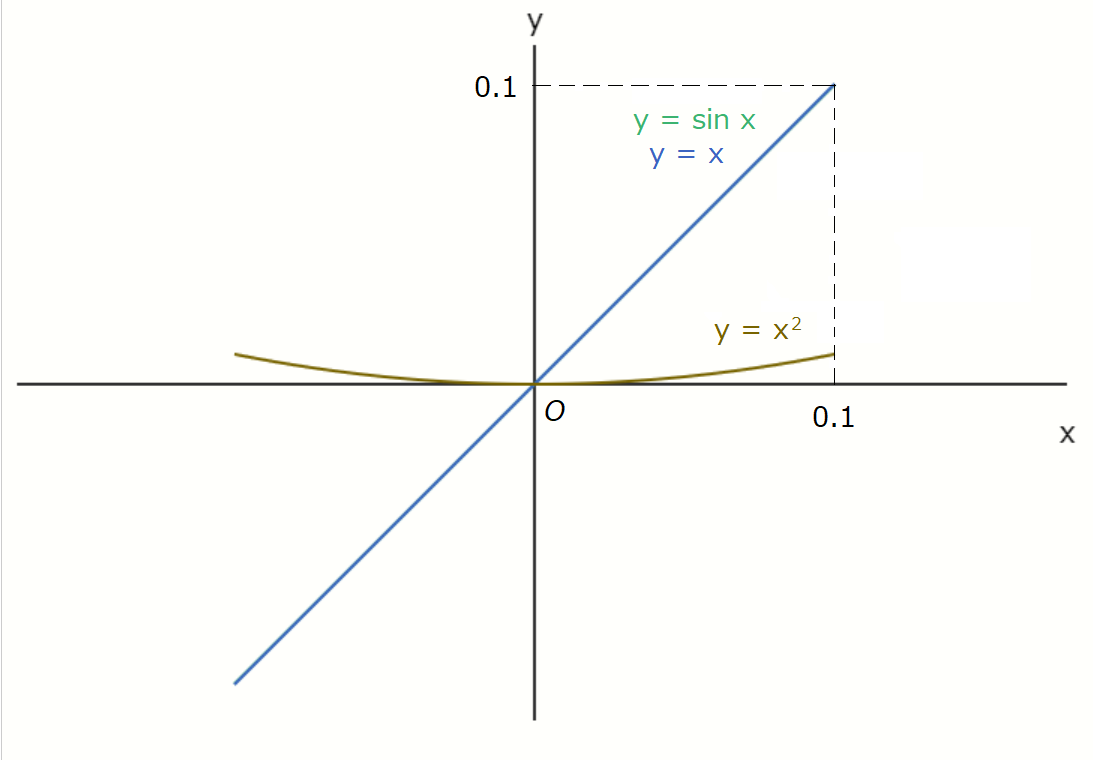

Yeah, that's right. Then, shall we look at a version of this graph magnified \( 10 \) times?

Nayumi

\( \sin x \) overlaps with \( x \) so perfectly that you can't even see it anymore... And \( x^2 \)

looks even flatter than before.

Kaya

Right. And if you keep zooming in forever, \( \sin x \) and \( x \) end up overlapping so closely that

you can't tell them apart anymore, whereas \( x^2 \) just flattens out completely.

That's the difference that creates the different behavior in the limits.

Nayumi

Dividing by zero is really tricky, huh.

Kaya

Yeah. Handling zero can be pretty tricky in mathematics.

Nayumi

Well, at least now I get the idea. Since we've covered the limit formula too, I guess that's it for

today?

Kaya

Yeah, let's wrap it up here for now.

Note: inverse trigonometric functions

\[ \begin{align}

\text{Inverse trigonometric functions}

\end{align}\]

When the domain of the function \( y = \sin x \) is restricted to \( \left[ -\pi/2, \pi/2 \right] \),

its inverse function is written as

\[ \begin{align}

y = \sin ^{-1} x \ \ \left( -1 \leq x \leq 1 \right)

\end{align}\]

Similarly, when the domain of \( y = \cos x \) is restricted to \( \left[ 0, \pi \right] \), its inverse

function is written as

\[ \begin{align}

y = \cos ^{-1} x \ \ \left( -1 \leq x \leq 1 \right)

\end{align}\]

Also, when the domain of \( y = \tan x \) is restricted to \( \left( -\pi/2, \pi/2 \right) \), its

inverse function is written as

\[ \begin{align}

y = \tan ^{-1} x \ \ \left( - \infty \leq x \leq \infty \right)

\end{align}\]

The functions \( \sin^{-1} x \), \( \cos^{-1} x \), and \( \tan^{-1} x \) are called inverse

trigonometric functions.

\( \sin ^{-1} x \) is read as “arc sine \( x \)” or “inverse sine \( x \).”

The same applies to \( \cos ^{-1} x \) and \( \tan ^{-1} x \).

Another notation for inverse trigonometric functions is:

\[ \begin{align}

\arcsin x,\ \arccos x,\ \arctan x

\end{align}\]

That is,

\[ \begin{align}

&\sin ^{-1} x = \arcsin x \\\\

&\cos ^{-1} x = \arccos x \\\\

&\tan ^{-1} x = \arctan x

\end{align}\]

These notations are often used interchangeably.

Nayumi

Even the same function can be written in various ways, huh.

Kaya

When reading a math book, we really need to make sure we understand what each symbol means.

References:

[1] James R. Newman, THE UNIVERSAL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MATHEMATICS, George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1964

[2] 石村園子, やさしく学べる微分積分, 共立出版, December 25, 1999

[3] 宮西正宜 23 others, 高等学校 数学Ⅱ 改訂版, 新興出版社啓林館, December 10, 2009

Previous

Ep. 3

Straight line and

conic section

Next

Ep. 5

Exponential and logarithmic functions