TABLE OF CONTENTS

・Partial fraction decomposition

Partial fraction decomposition

Partial fraction decomposition is the operation of splitting a fraction into two parts.

Let’s start with the basic form and consider the following decomposition.

We’re looking for \( k \) that satisfies

\[ \frac{1}{ab} = k \left( \frac{1}{a} + \frac{1}{b} \right). \]

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{1}{ab} &= k \left( \frac{1}{a} + \frac{1}{b} \right) \\\\

\frac{1}{ab} &= k \left( \frac{a+b}{ab} \right)

\end{align}\]

Compare both sides,

\[ 1 = k \left( a+b \right) \]

Thus,

\[ k = \frac{1}{a+b} \]

\[ \frac{1}{ab} = \frac{1}{a+b} \left( \frac{1}{a} + \frac{1}{b} \right) = \frac{1}{a \left( a + b

\right) } + \frac{1}{b \left( a + b \right)} \]

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{1}{a \left( a + b \right) } &= \frac{1}{a + \left( a + b \right)} \left( \frac{1}{a} +

\frac{1}{a+b} \right) \\\\

&= \frac{1}{2a+b} \left( \frac{1}{a} + \frac{1}{a+b} \right) \\\\

\frac{1}{b \left( a + b \right)} &= \frac{1}{b + \left( a + b \right)} \left( \frac{1}{b} +

\frac{1}{a+b} \right) \\\\

&= \frac{1}{a + 2b} \left( \frac{1}{b} + \frac{1}{a+b} \right)

\end{align}\]

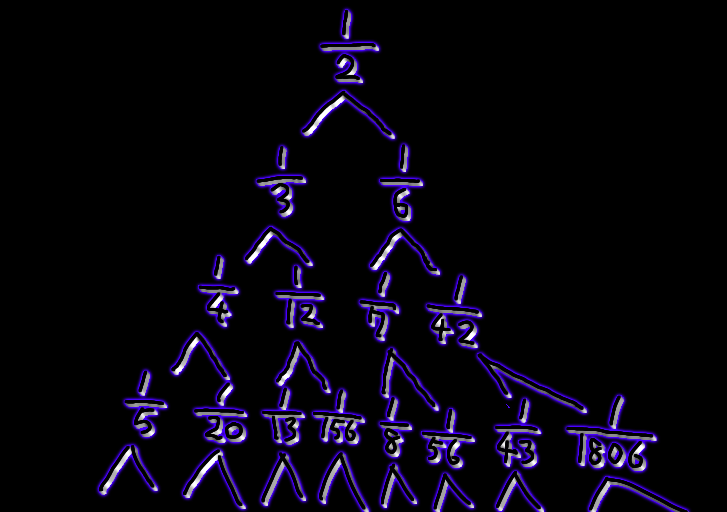

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{1}{2} &= \frac{1}{1 \cdot 3} + \frac{1}{2 \cdot 3} \\\\

&= \frac{1}{1 \cdot 4} + \frac{1}{3 \cdot 4} + \frac{1}{2 \cdot 5} + \frac{1}{3 \cdot 5} \\\\

&= \frac{1}{1 \cdot 5} + \frac{1}{4 \cdot 5} + \frac{1}{3 \cdot 7} + \frac{1}{4 \cdot 7} + \frac{1}{2

\cdot 7} + \frac{1}{5 \cdot 7} + \frac{1}{3 \cdot 8} + \frac{1}{5 \cdot 8} \\\\

&= \ldots

\end{align}\]

We’re looking for \( p \) and \( q \) that satisfy

\[ \frac{1}{\left( ax+b \right) \left( cx+d \right)} = \left( \frac{p}{ax+b} + \frac{q}{cx+d} \right) \]

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{1}{\left( ax+b \right) \left( cx+d \right)} &= \left( \frac{p}{ax+b} + \frac{q}{cx+d} \right) \\\\

&= \frac{p \left( cx+d \right) + q \left( ax+b \right)}{\left( ax+b \right) \left( cx+d \right)} \\\\

&= \frac{\left( cp + aq \right) x + dp + bq}{\left( ax+b \right) \left( cx+d \right)}

\end{align}\]

As before, we compare the left-hand side and the right-hand side.

However, this time we want to find \( p \) and \( q \), so we need to set up two equations involving these

variables.

Meanwhile, \( x \) also appears in the denominators. If we were to express it in terms of the other symbols in the denominators, such as \( a \) or \( b \), it would effectively change the denominators themselves — which would be inconvenient.

Therefore, we handle this by setting the coefficient of \( x \) in the numerator equal to 0, and the part independent of \( x \) equal to 1.

Meanwhile, \( x \) also appears in the denominators. If we were to express it in terms of the other symbols in the denominators, such as \( a \) or \( b \), it would effectively change the denominators themselves — which would be inconvenient.

Therefore, we handle this by setting the coefficient of \( x \) in the numerator equal to 0, and the part independent of \( x \) equal to 1.

\[ \begin{align}

[1] \ \ \ \ cp + aq &= 0 \\\\

[2] \ \ \ \ dp + bq &= 1

\end{align}\]

From [1], we have

\[ q = - \frac{c}{a} p \]

Substituting this into [2], we get

\[ \begin{align}

dp - \frac{bc}{a} p &= 1 \\\\

p \left( d - \frac{bc}{a} \right) &= 1 \\\\

p \cdot \frac{ad - bc}{a} &= 1 \\\\

p &= \frac{a}{ad - bc}

\end{align}\]

Therefore,

\[ \begin{align}

q &= - \frac{c}{a} p \\\\

&= - \frac{c}{a} \cdot \frac{a}{ad - bc} \\\\

&= - \frac{c}{ad - bc}

\end{align}\]

\[ \begin{align}

\frac{1}{\left( ax+b \right) \left( cx+d \right)} &= \left( \frac{p}{ax+b} + \frac{q}{cx+d} \right) \\\\

&= \left( \frac{\frac{a}{ad - bc}}{ax+b} + \frac{- \frac{c}{ad - bc}}{cx+d} \right) \\\\

&= \frac{1}{ad - bc} \left( \frac{a}{ax+b} - \frac{c}{cx+d} \right)

\end{align}\]

References:

[1] Partial fraction decomposition, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Partial_fraction_decomposition,

October 20, 2025